1. What did young Augustine pray for?

2. What did Augustine believe about God, during his Manichaean period?

3. How did Augustine differ from Plato and Aristotle regarding time and creation?

4. What does Russell find odd about Augustine's preoccupations, on the eve of the dark ages?

==

5. Platonic philosophy had a greater hold on Boethius than what?

6. What obsession did Boethius not share with Augustine?

==

PW

7. It's impossible to be what, according to Gros, when walking?

8. What turns everything into nonsenese?

DQ

- Do you agree with Russell that Augustine's extreme sense of sin made him and his philosophy stern and inhuman? 345

- Do sin and moral evil adquately explain "how a beneficent Deity can cause men to suffer"? 346

- How does free will explain suffering due to natural phenomena like earthquakes, hurricanes, and disease?

- Do you agree that "even infants... are full of sin"? 347

- What do you think of Manicheanism?

- Does it solve the mystery of existence to say that time and space were created when the world was created, that God "preceded" both, and that there was no "sooner"? 353

- Why do you think Boethius, a Christian, called his book Consolation of Philosophy (not Theology)?

- Why should Boethius' pantheism have shocked Christians? 370

- Do you enjoy solitude and alone-time? Or do you hate being by yourself?

- Do you ever converse with yourself? Is it a dialogue between body and soul, between different aspects of your self, or what?

- Do you enjoy silence, or must you fill every moment with chatter, music, background noise, etc.? Do you ever try to just be, wordlessly, without internal narration or commentary?

Old posts-

Augustine (LH); WATCH:Augustine (SoL); LISTEN:Neuroscience & free will (HI)

1. (T/F) Augustine was a chaste and pious youth, converting to Christianity while still a boy.

2. Augustine's early "Manicheaean" solution to the problem of suffering was to claim what about God?

3. Augustine's later solutions were the Free Will Defense and what?

4. Like Maimonides and Avicenna, Augustine represents what tendency of religious medieval thinkers between the fifth and fifteenth centuries?

5. What's the difference between "natural" and "moral" evil? Give an example of each.

6. Augustine thought that if God had programmed humans always to be good, we'd be like what?

BONUS: Which cartoon character says free will is an illusion?

BONUS: What recent controversialist said "good" means supportive of human well-being and flourishing?

DQ:

1. Is it better to embrace (or renounce) religious faith early in life, or to "sow your wild oats" and enjoy a wide experience of the world before committing to any particular tradition or belief? Were you encouraged by adults, in childhood, to make a public profession of faith? If so, did you understand what that meant or entailed?

2. Does the concept of a never-ending struggle between good and evil appeal to you? Does it make sense, in the light of whatever else you believe? Would there be anything "wrong" with a world in which good was already triumphant, happiness for all already secured, kindness and compassion unrivaled by hatred and cruelty?

3. Do you find the concept of Original Sin compelling, difficult, unfair, or dubious? In general, do we "inherit the sins of our fathers (and mothers)"? If yes, give examples and explain.

4. Should religious traditions attempt to combine with, or assimilate themselves to, philosophical traditions? What do religion and philosophy generally have in common, and in what ways are they different?

5. Does the free will defense work, even to the extent of explaining "moral" evil? Is there in fact a logical contradiction between the concept of free will and an omniscient deity? Why or why not?

6. Would we be better off without a belief in free will?

Excerpt:

1

AUGUSTINE OF HIPPO (354–430)

Beware lest any man spoil you through philosophy and vain deceit, after the tradition of men, after the rudiments of the world, and not after Christ.

—Paul, Colossians 2:8

AUGUSTINE, a teenager studying in Carthage in the 370s, begins to ponder what he will one day consider the inevitable shortcomings of human philosophy ungrounded in the word of God. This process begins, as Augustine will later recount in his Confessions, when he reads Cicero’sHortensius, written around 45 b.c.e. The young scholar, unacquainted with either Jewish or Christian Scripture, takes away the (surely unintended) lesson from the pagan Cicero that only faith—a faith that places the supernatural above the natural—can satisfy the longing for wisdom.

“But, O Light of my heart,” Augustine wrote to his god in Confessions (c. 397), “you know that at that time, although Paul’s words were not known to me, the only thing that pleased me in Cicero’s book was his advice not simply to admire one or another of the schools of philosophy, but to love wisdom itself, whatever it might be. . . . These were the words which excited me and set me burning with fire, and the only check to this blaze of enthusiasm was that they made no mention of the name of Christ.”

The only check? To me, this passage from Confessions has always sounded like the many rewritings of personal history intended to conform the past to the author’s current beliefs and status in life—which in Augustine’s case meant being an influential bishop of an ascendant church that would tolerate no dissent grounded in other religious or secular philosophies. By the time he writes Confessions, Augustine seems a trifle embarrassed about having been so impressed, as a young man, by a pagan writer. So he finds a way to absolve himself of the sin of attraction to small-“c” catholic, often secular intellectual interests by limiting Cicero to his assigned role as one step in a fourth-century boy’s journey toward capital-“C” Catholicism. It is the adult Augustine who must reconcile his enthusiasm for Cicero with the absence of the name of Christ; there is no reason why this should have bothered the pagan adolescent Augustine at all. Nevertheless, no passage in the writings of the fathers of the church, or in any personal accounts of the intellectual and emotional process of conversion, explains more lucidly (albeit indirectly) why the triumph of Christianity inevitably begins with that other seeker on the road to Damascus. It is Paul, after all, not Jesus or the authors of the Gospels, who merits a mention in Augustine’s explanation of how his journey toward the one true faith was set in motion by a pagan.

It is impossible to consider Augustine, the second most important convert in the theological firmament of the early Christian era, without giving Paul his due. But let us leave Saul—he was still Saul then—as he awakes from a blow on his head to hear a voice from the heavens calling him to rebirth in Christ. Saul did not have any established new religion to convert to, but Augustine was converting to a faith with financial and political influence, as well as a spiritual message for the inhabitants of a decaying empire. Augustine’s journey from paganism to Christianity was a philosophical and spiritual struggle lasting many years, but it also exemplified the many worldly, secular influences on conversion in his and every subsequent era. These include mixed marriages; political instability that creates the perception and the reality of personal insecurity; and economic conditions that provide a space for new kinds of fortunes and the possibility of financial support for new religious institutions.

Augustine told us all about his struggle, within its social context, in Confessions—which turned out to be a best-seller for the ages. This was a new sort of book, even if it was a highly selective recounting of experience (like all memoirs) rather than a “tell-all” autobiography in the modern sense. Its enduring appeal, after a long break during the Middle Ages, lies not in its literary polish, intellectuality, or prayerfulness—though the memoir is infused with these qualities—but in its preoccupation with the individual’s relationship to and responsibility for sin and evil. As much as Augustine’s explorations constitute an individual journey—and have been received as such by generations of readers—the journey unfolds in an upwardly mobile, religiously divided family that was representative of many other people finding and shaping new ways to make a living; new forms of secular education; and new institutions of worship in a crumbling Roman civilization.

After a lengthy quest venturing into regions as wild as those of any modern religious cults, Augustine told the story of his spiritual odyssey when he was in his forties. His subsequent works, including The City of God, are among the theological pillars of Christianity, butConfessions is the only one of his books read widely by anyone but theologically minded intellectuals (or intellectual theologians). In the fourth and early fifth centuries, Christian intellectuals with both a pagan and a religious education, like the friends and mentors Augustine discusses in the book, provided the first audience for Confessions. That audience would probably not have existed a century earlier, because literacy—a secular prerequisite for a serious education in both paganism and Christianity—had expanded among members of the empire’s bourgeois class by the time Augustine was born. The Christian intellectuals who became Augustine’s first audience may have been more interested than modern readers in the theological framework of the autobiography (though they, too, must have been curious about the distinguished bishop’s sex life). ButConfessions has also been read avidly, since the Renaissance, by successive generations of humanist scholars (religious and secular); Enlightenment skeptics; nineteenth-century Romantics; psychotherapists; and legions of the prurient, whether religious believers or nonbelievers. Everyone, it seems, loves the tale of a great sinner turned into a great saint.

In my view, Augustine was neither a world-class sinner nor a saint, but his drama of sin and repentance remains a real page-turner. Here & Now==

An old post-

Augustine & string theory

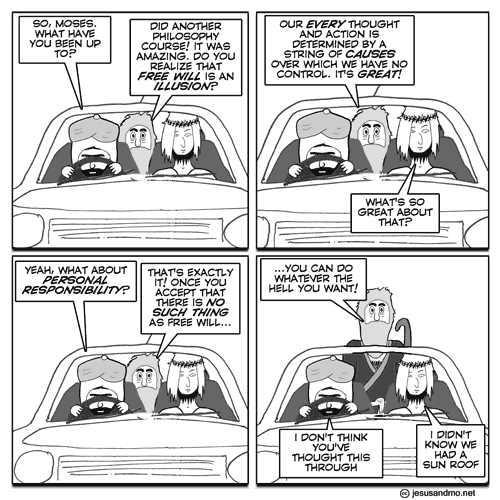

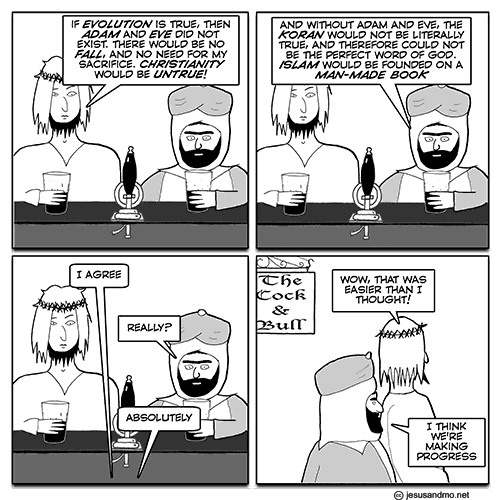

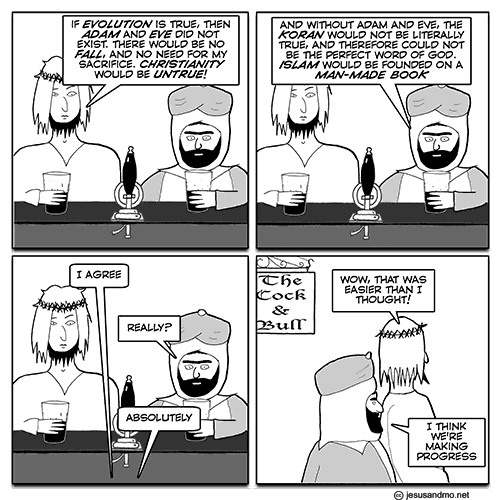

Is anyone, from God on down, “pulling our strings”? We’d not be free if they were, would we? If you say we would, what do you mean by “free”? Jesus and Mo have puzzled this one, behind the wheel with with Moses and with "Free Willy." But as usual, the Atheist Barmaid is unpersuaded.

(As I always must say, when referencing this strip: that’s not Jesus of Nazareth, nor is it the Prophet Mohammed, or the sea-parter Moses; and neither I nor Salman Rushdie, the Dutch cartoonists, the anonymous Author, or anyone else commenting on religion in fictional media are blasphemers. We're all just observers exercising our "god-given" right of free speech, which of course extends no further than the end of a fist and the tip of a nose. We'll be celebrating precisely that, and academic freedom, when we line up to take turns reading the Constitution this morning.

No, they’re just a trio of cartoonish guys who often engage in banter relevant to our purposes in CoPhi. It’s just harmless provocation, and fun. But if it makes us think, it’s useful.)

Augustine proposed a division between the “city of god” and the “earthly city” of humanity, thus excluding many of us from his version of the cosmos. “These two cities of the world, which are doomed to coexist intertwined until the Final Judgment, divide the world’s inhabitants.” SEP

And of course he believed in hell, raising the stakes for heaven and the judicious free will he thought necessary to get there even higher. If there's no such thing as free will, though, how can you do "whatever the hell you want"? But, imagine there's no heaven or hell. What then? Some of us think that's when free will becomes most useful to members of a growing, responsible species.

Someone posted the complaint on our class message board that it's not clear what "evil" means, in the context of our Little History discussion of Augustine. But I think this is clear enough: "there is a great deal of suffering in the world," some of it proximally caused by crazy, immoral/amoral, armed and dangerous humans behaving badly, much more of it caused by earthquakes, disease, and other "natural" causes. All of it, on the theistic hypothesis, is part and parcel of divinely-ordered nature.

Whether or not some suffering is ultimately beneficial, character-building, etc., and from whatever causes, "evil" means the suffering that seems gratuitously destructive of innocent lives. Some of us "can't blink the evil out of sight," in William James's words, and thus can't go in for theistic (or other) schemes of "vicarious salvation." We think it's the responsibility of humans to use their free will (or whatever you prefer to call ameliorative volitional action) to reduce the world's evil and suffering. Take a sad song and make it better.

Note the Manichaean strain in Augustine, and the idea that "evil comes from the body." That's straight out of Plato. The world of Form and the world of perfect heavenly salvation thus seem to converge. If you don't think "body" is inherently evil, if in fact you think material existence is pretty cool (especially considering the alternative), this view is probably not for you. Nor if you can't make sense of Original Sin, that most "difficult" contrivance of the theology shop.

"Augustine had felt the hidden corrosive effect of Adam's Fall, like the worm in the apple, firsthand," reminds Arthur Herman. His prayer for personal virtue "but not yet" sounds funny but was a cry of desperation and fear.

Bertrand Russell, we know, was not a Christian. But he was a bit of a fan of Augustine the philosopher (as distinct from the theologian), on problems like time.

As for Augustine the theologian and Saint-in-training, Russell's pen drips disdain.

That's an allusive segue to today's additional discussion of Aristotelian virtue ethics, in its turn connected with the contradictions inherent in the quest to bend invariably towards Commandments. "Love your neighbor": must that mean, let your neighbor suffer a debilitating terminal illness you could pull the plug on? Or is the "Christian" course, sometimes, to put an end to it?

We also read today of Hume's Law, Moore's Naturalistic Fallacy, the old fact/value debate. Sam Harris is one of the most recent controversialists to weigh in on the issue, arguing that "good" means supportive of human well-being and flourishing, which are in turn based on solid facts. "The answer to the question, 'What should I believe, and why should I believe it?' is generally a scientific one..." Brain Science and Human Values

Also: ethical relativism, meta-ethics, and more. And maybe we'll have time to squeeze in consideration of the perennial good-versus-evil trope. Would there be anything "wrong" with a world in which good was already triumphant, happiness for all already secured, kindness and compassion unrivaled by hatred and cruelty? I think it might be just fine. Worth a try, anyway. Where can I vote for that?

==

Boethius (LH); Consolation of Philosophy Bk V (* below); LISTEN: Religious freedom as constraint (HI) and IOT [this is a late addition, not required but strongly recommended]; WATCH: Boethius & Philosophy... dawn post: Boethius... **Anselm & Aquinas (LH); WATCH: Aquinas & 1st Cause (HI) LISTEN:Anthony Kenny on Aquinas' Ethics (PB)....Podcast

1. Who consoles Boethius in his prison cell but also reprimands him for having forgotten her?

2. What paradox puzzles and perplexes Boethius?

3. Why does "Philosophy" say divine foreknowledge does not rob us of free will?

4. Why did Anselm conclude that God must exist?

5. Why did Aquinas think there couldn't be an infinite regress of causes?

6. Is "Nothing" obviously the best answer to "What caused the cosmos?

DQ

==

'Since, then, every mode of judgment comprehends its objects conformably to its own nature, and since God abides for ever in an eternal present, His knowledge, also transcending all movement of time, dwells in the simplicity of its own changeless present, and, embracing the whole infinite sweep of the past and of the future, contemplates all that falls within its simple cognition as if it were now taking place. And therefore, if thou wilt carefully consider that immediate presentment whereby it discriminates all things, thou wilt more rightly deem it not foreknowledge as of something future, but knowledge of a moment that never passes. For this cause the name chosen to describe it is not prevision, but providence, because, since utterly removed in nature from things mean and trivial, its outlook embraces all things as from some lofty height. Why, then, dost thou insist that the things which are surveyed by the Divine eye are involved in necessity, whereas clearly men impose no necessity on things which they see? Does the act of vision add any necessity to the things which thou seest before thy eyes?'

'Assuredly not.'

And yet, if we may without unfitness compare God's present and man's, just as ye see certain things in this your temporary present, so does He see all things in His eternal present. Wherefore this Divine anticipation changes not the natures and properties of things, and it beholds things present before it, just as they will hereafter come to pass in time. Nor does it confound things in its judgment, but in the one mental view distinguishes alike what will come necessarily and what without necessity. For even as ye, when at one and the same time ye see a man walking on the earth and the sun rising in the sky, distinguish between the two, though one glance embraces both, and judge the former voluntary, the latter necessary action: so also the Divine vision in its universal range of view does in no wise confuse the characters of the things which are present to its regard, though future in respect of time. Whence it follows that when it perceives that something will come into existence, and yet is perfectly aware that this is unbound by any necessity, its apprehension is not opinion, but rather knowledge based on truth. And if to this thou sayest that what God sees to be about to come to pass cannot fail to come to pass, and that what cannot fail to come to pass happens of necessity, and wilt tie me down to this word necessity, I will acknowledge that thou affirmest a most solid truth, but one which scarcely anyone can approach to who has not made theDivine his special study. For my answer would be that the same future event is necessary from the standpoint of Divine knowledge, but when considered in its own nature it seems absolutely free and unfettered. So, then, there are two necessities—one simple, as that men are necessarily mortal; the other conditioned, as that, if you know that someone is walking, he must necessarily be walking. For that which is known cannot indeed be otherwise than as it is known to be, and yet this fact by no means carries with it that other simple necessity. For the former necessity is not imposed by the thing's own proper nature, but by the addition of a condition. No necessity compels one who is voluntarily walking to go forward, although it is necessary for him to go forward at the moment of walking. In the same way, then, if Providence sees anything as present, that must necessarily be, though it is bound by no necessity of nature. Now, God views as present those coming events which happen of free will. These, accordingly, from the standpoint of the Divine vision are made necessary conditionally on the Divine cognizance; viewed, however, in themselves, they desist not from the absolute freedom naturally theirs. Accordingly, without doubt, all things will come to pass which God foreknows as about to happen, but of these certain proceed of free will; and though these happen, yet by the fact of their existence they do not lose their proper nature, in virtue of which before they happened it was really possible that they might not have come to pass.

'What difference, then, does the denial of necessity make, since, through their being conditioned by Divine knowledge, they come to pass as if they were in all respects under the compulsion of necessity? This difference, surely, which we saw in the case of the instances I formerly took, the sun's rising and the man's walking; which at the moment of their occurrence could not but be taking place, and yet one of them before it took place was necessarily obliged to be, while the other was not so at all. So likewise the things which to God are present without doubt exist, but some of them come from the necessity of things, others from the power of the agent. Quite rightly, then, have we said that these things are necessary if viewed from the standpoint of the Divine knowledge; but if they are considered in themselves, they are free from the bonds of necessity, even as everything which is accessible to sense, regarded from the standpoint of Thought, is universal, but viewed in its own nature particular. "But," thou wilt say, "if it is in my power to change my purpose, I shall make void providence, since I shall perchance change something which comes within its foreknowledge." My answer is: Thou canst indeed turn aside thy purpose; but since the truth of providence is ever at hand to see that thou canst, and whether thou dost, and whither thou turnest thyself, thou canst not avoid the Divine foreknowledge, even as thou canst not escape the sight of a present spectator, although of thy free will thou turn thyself to various actions. Wilt thou, then, say: "Shall the Divine knowledge be changed at my discretion, so that, when I will this or that, providence changes its knowledge correspondingly?"

'Surely not.'

'True, for the Divine vision anticipates all that is coming, and transforms and reduces it to the form of its own present knowledge, and varies not, as thou deemest, in its foreknowledge, alternating to this or that, but in a single flash it forestalls and includes thy mutations without altering. And this ever-present comprehension and survey of all things God has received, not from the issue of future events, but from the simplicity of His own nature. Hereby also is resolved the objection which a little while ago gave thee offence—that our doings in the future were spoken of as if supplying the cause of God's knowledge. For this faculty of knowledge, embracing all things in its immediate cognizance, has itself fixed the bounds of all things, yet itself owes nothing to what comes after.

'And all this being so, the freedom of man's will stands unshaken, and laws are not unrighteous, since their rewards and punishments are held forth to wills unbound by any necessity. God, who foreknoweth all things, still looks down from above, and the ever-present eternity of His vision concurs with the future character of all our acts, and dispenseth to the good rewards, to the bad punishments. Our hopes and prayers also are not fixed on God in vain, and when they are rightly directed cannot fail of effect. Therefore, withstand vice, practise virtue, lift up your souls to right hopes, offer humble prayers to Heaven. Great is the necessity of righteousness laid upon you if ye will not hide it from yourselves, seeing that all your actions are done before the eyes of a Judge who seeth all things.'

EPILOGUE. Within a short time of writing 'The Consolation of Philosophy,' Boethius died by a cruel death. As to the manner of his death there is some uncertainty. According to one account, he was cut down by the swords of the soldiers before the very judgment-seat of Theodoric; according to another, a cord was first fastened round his forehead, and tightened till 'his eyes started'; he was then killed with a club.

==

An old post

Tuesday, February 17, 2015

Boethius & Bentham & animal rights

Today in CoPhi it's the pagan/stoic/Christian/Platonist martyr Boethius, and then the rights of animals.

We saw last time that Bertrand Russell had little regard for how Augustine, despite his philosophical sophistication when it came to hard-nut conceptual problems like time, ironically squandered much of his own on a preoccupation with sin, chastity, and staying out of hell.

Russell liked Boethius, or aspects of his thought at least. Boethius was also perplexed by time, and initially unimpressed by the alleged capacity of timeless divinity to accommodate both omniscience and free will. Like Russell, I'm struck by this "singular" thinker's ability to contemplate happiness (he thought all genuinely happy people are gods) while practically darkening death's door.

Boethius was consoled by the thought that God’s foreknowledge of everything, including the fact that Boethius himself (among too many others) would be unjustly imprisoned and tortured to death, in no way impaired his (Boethius’s) freedom or god's perfection. Consoled. Comforted.Calmed. Reconciled.

That’s apparently because God knows things timelessly, sees everything “in a go.” I don’t think that would really make me feel any better, in my prison cell. The real consolation of philosophycomes when it contributes to the liberation of mind and body (one thing, not two). But it’s still very cool to imagine Philosophy a comfort-woman, reminding us of our hard-earned wisdom when the going gets impossible.

And then, of course, they killed him. The list of martyred philosophers grows. And let’s not forgetHypatia and Bruno. [Russell] The problem of suffering (“evil”) was very real to them, as it is to so many of our fellow world-citizens. You can’t chalk it all up to free will. But can we even chalk torture or any other inflicted choice up to it, given the full scope of a genuinely omniscient creator’s knowledge? If He already knows what I’m going to do unto others and what others will do unto me, am I in any meaningful sense a free agent who might have done otherwise? The buck stops where?

For those keeping score, add Boethius to Aristotle's column.

[Christians 2, Philosophers 0... Christians & Muslims...JandMoandPaul...Mystics, scholastics, Ferengi... faith & reason...]

1. (T/F) Augustine was a chaste and pious youth, converting to Christianity while still a boy.

2. Augustine's early "Manicheaean" solution to the problem of suffering was to claim what about God?

3. Augustine's later solutions were the Free Will Defense and what?

4. Like Maimonides and Avicenna, Augustine represents what tendency of religious medieval thinkers between the fifth and fifteenth centuries?

5. What's the difference between "natural" and "moral" evil? Give an example of each.

6. Augustine thought that if God had programmed humans always to be good, we'd be like what?

BONUS: Which cartoon character says free will is an illusion?

BONUS: What recent controversialist said "good" means supportive of human well-being and flourishing?

DQ:

1. Is it better to embrace (or renounce) religious faith early in life, or to "sow your wild oats" and enjoy a wide experience of the world before committing to any particular tradition or belief? Were you encouraged by adults, in childhood, to make a public profession of faith? If so, did you understand what that meant or entailed?

2. Does the concept of a never-ending struggle between good and evil appeal to you? Does it make sense, in the light of whatever else you believe? Would there be anything "wrong" with a world in which good was already triumphant, happiness for all already secured, kindness and compassion unrivaled by hatred and cruelty?

3. Do you find the concept of Original Sin compelling, difficult, unfair, or dubious? In general, do we "inherit the sins of our fathers (and mothers)"? If yes, give examples and explain.

4. Should religious traditions attempt to combine with, or assimilate themselves to, philosophical traditions? What do religion and philosophy generally have in common, and in what ways are they different?

5. Does the free will defense work, even to the extent of explaining "moral" evil? Is there in fact a logical contradiction between the concept of free will and an omniscient deity? Why or why not?

6. Would we be better off without a belief in free will?

Excerpt:

1

AUGUSTINE OF HIPPO (354–430)

Beware lest any man spoil you through philosophy and vain deceit, after the tradition of men, after the rudiments of the world, and not after Christ.

—Paul, Colossians 2:8

AUGUSTINE, a teenager studying in Carthage in the 370s, begins to ponder what he will one day consider the inevitable shortcomings of human philosophy ungrounded in the word of God. This process begins, as Augustine will later recount in his Confessions, when he reads Cicero’sHortensius, written around 45 b.c.e. The young scholar, unacquainted with either Jewish or Christian Scripture, takes away the (surely unintended) lesson from the pagan Cicero that only faith—a faith that places the supernatural above the natural—can satisfy the longing for wisdom.

“But, O Light of my heart,” Augustine wrote to his god in Confessions (c. 397), “you know that at that time, although Paul’s words were not known to me, the only thing that pleased me in Cicero’s book was his advice not simply to admire one or another of the schools of philosophy, but to love wisdom itself, whatever it might be. . . . These were the words which excited me and set me burning with fire, and the only check to this blaze of enthusiasm was that they made no mention of the name of Christ.”

The only check? To me, this passage from Confessions has always sounded like the many rewritings of personal history intended to conform the past to the author’s current beliefs and status in life—which in Augustine’s case meant being an influential bishop of an ascendant church that would tolerate no dissent grounded in other religious or secular philosophies. By the time he writes Confessions, Augustine seems a trifle embarrassed about having been so impressed, as a young man, by a pagan writer. So he finds a way to absolve himself of the sin of attraction to small-“c” catholic, often secular intellectual interests by limiting Cicero to his assigned role as one step in a fourth-century boy’s journey toward capital-“C” Catholicism. It is the adult Augustine who must reconcile his enthusiasm for Cicero with the absence of the name of Christ; there is no reason why this should have bothered the pagan adolescent Augustine at all. Nevertheless, no passage in the writings of the fathers of the church, or in any personal accounts of the intellectual and emotional process of conversion, explains more lucidly (albeit indirectly) why the triumph of Christianity inevitably begins with that other seeker on the road to Damascus. It is Paul, after all, not Jesus or the authors of the Gospels, who merits a mention in Augustine’s explanation of how his journey toward the one true faith was set in motion by a pagan.

It is impossible to consider Augustine, the second most important convert in the theological firmament of the early Christian era, without giving Paul his due. But let us leave Saul—he was still Saul then—as he awakes from a blow on his head to hear a voice from the heavens calling him to rebirth in Christ. Saul did not have any established new religion to convert to, but Augustine was converting to a faith with financial and political influence, as well as a spiritual message for the inhabitants of a decaying empire. Augustine’s journey from paganism to Christianity was a philosophical and spiritual struggle lasting many years, but it also exemplified the many worldly, secular influences on conversion in his and every subsequent era. These include mixed marriages; political instability that creates the perception and the reality of personal insecurity; and economic conditions that provide a space for new kinds of fortunes and the possibility of financial support for new religious institutions.

Augustine told us all about his struggle, within its social context, in Confessions—which turned out to be a best-seller for the ages. This was a new sort of book, even if it was a highly selective recounting of experience (like all memoirs) rather than a “tell-all” autobiography in the modern sense. Its enduring appeal, after a long break during the Middle Ages, lies not in its literary polish, intellectuality, or prayerfulness—though the memoir is infused with these qualities—but in its preoccupation with the individual’s relationship to and responsibility for sin and evil. As much as Augustine’s explorations constitute an individual journey—and have been received as such by generations of readers—the journey unfolds in an upwardly mobile, religiously divided family that was representative of many other people finding and shaping new ways to make a living; new forms of secular education; and new institutions of worship in a crumbling Roman civilization.

After a lengthy quest venturing into regions as wild as those of any modern religious cults, Augustine told the story of his spiritual odyssey when he was in his forties. His subsequent works, including The City of God, are among the theological pillars of Christianity, butConfessions is the only one of his books read widely by anyone but theologically minded intellectuals (or intellectual theologians). In the fourth and early fifth centuries, Christian intellectuals with both a pagan and a religious education, like the friends and mentors Augustine discusses in the book, provided the first audience for Confessions. That audience would probably not have existed a century earlier, because literacy—a secular prerequisite for a serious education in both paganism and Christianity—had expanded among members of the empire’s bourgeois class by the time Augustine was born. The Christian intellectuals who became Augustine’s first audience may have been more interested than modern readers in the theological framework of the autobiography (though they, too, must have been curious about the distinguished bishop’s sex life). ButConfessions has also been read avidly, since the Renaissance, by successive generations of humanist scholars (religious and secular); Enlightenment skeptics; nineteenth-century Romantics; psychotherapists; and legions of the prurient, whether religious believers or nonbelievers. Everyone, it seems, loves the tale of a great sinner turned into a great saint.

In my view, Augustine was neither a world-class sinner nor a saint, but his drama of sin and repentance remains a real page-turner. Here & Now==

An old post-

Augustine & string theory

Is anyone, from God on down, “pulling our strings”? We’d not be free if they were, would we? If you say we would, what do you mean by “free”? Jesus and Mo have puzzled this one, behind the wheel with with Moses and with "Free Willy." But as usual, the Atheist Barmaid is unpersuaded.

(As I always must say, when referencing this strip: that’s not Jesus of Nazareth, nor is it the Prophet Mohammed, or the sea-parter Moses; and neither I nor Salman Rushdie, the Dutch cartoonists, the anonymous Author, or anyone else commenting on religion in fictional media are blasphemers. We're all just observers exercising our "god-given" right of free speech, which of course extends no further than the end of a fist and the tip of a nose. We'll be celebrating precisely that, and academic freedom, when we line up to take turns reading the Constitution this morning.

No, they’re just a trio of cartoonish guys who often engage in banter relevant to our purposes in CoPhi. It’s just harmless provocation, and fun. But if it makes us think, it’s useful.)

Augustine proposed a division between the “city of god” and the “earthly city” of humanity, thus excluding many of us from his version of the cosmos. “These two cities of the world, which are doomed to coexist intertwined until the Final Judgment, divide the world’s inhabitants.” SEP

And of course he believed in hell, raising the stakes for heaven and the judicious free will he thought necessary to get there even higher. If there's no such thing as free will, though, how can you do "whatever the hell you want"? But, imagine there's no heaven or hell. What then? Some of us think that's when free will becomes most useful to members of a growing, responsible species.

Someone posted the complaint on our class message board that it's not clear what "evil" means, in the context of our Little History discussion of Augustine. But I think this is clear enough: "there is a great deal of suffering in the world," some of it proximally caused by crazy, immoral/amoral, armed and dangerous humans behaving badly, much more of it caused by earthquakes, disease, and other "natural" causes. All of it, on the theistic hypothesis, is part and parcel of divinely-ordered nature.

Whether or not some suffering is ultimately beneficial, character-building, etc., and from whatever causes, "evil" means the suffering that seems gratuitously destructive of innocent lives. Some of us "can't blink the evil out of sight," in William James's words, and thus can't go in for theistic (or other) schemes of "vicarious salvation." We think it's the responsibility of humans to use their free will (or whatever you prefer to call ameliorative volitional action) to reduce the world's evil and suffering. Take a sad song and make it better.

Note the Manichaean strain in Augustine, and the idea that "evil comes from the body." That's straight out of Plato. The world of Form and the world of perfect heavenly salvation thus seem to converge. If you don't think "body" is inherently evil, if in fact you think material existence is pretty cool (especially considering the alternative), this view is probably not for you. Nor if you can't make sense of Original Sin, that most "difficult" contrivance of the theology shop.

"Augustine had felt the hidden corrosive effect of Adam's Fall, like the worm in the apple, firsthand," reminds Arthur Herman. His prayer for personal virtue "but not yet" sounds funny but was a cry of desperation and fear.

Like Aristotle, Augustine believed that the quality of life we lead depends on the choices we make. The tragedy is that left to our own devices - and contrary to Aristotle - most of those choices will be wrong. There can be no true morality without faith and no faith without the presence of God. The Cave and the Light

Bertrand Russell, we know, was not a Christian. But he was a bit of a fan of Augustine the philosopher (as distinct from the theologian), on problems like time.

As for Augustine the theologian and Saint-in-training, Russell's pen drips disdain.

It is strange that the last men of intellectual eminence before the dark ages were concerned, not with saving civilization or expelling the barbarians or reforming the abuses of the administration, but with preaching the merit of virginity and the damnation of unbaptized infants.Funny, how the preachers of the merit of virginity so often come late - after exhausting their stores of wild oats - to their chaste piety. Not exactly paragons of virtue or character, these Johnnys Come Lately. On the other hand, it's possible to profess a faith you don't understand much too soon. My own early Sunday School advisers pressured and frightened me into "going forward" at age 6, lest I "die before I wake" one night and join the legions of the damned.

That's an allusive segue to today's additional discussion of Aristotelian virtue ethics, in its turn connected with the contradictions inherent in the quest to bend invariably towards Commandments. "Love your neighbor": must that mean, let your neighbor suffer a debilitating terminal illness you could pull the plug on? Or is the "Christian" course, sometimes, to put an end to it?

We also read today of Hume's Law, Moore's Naturalistic Fallacy, the old fact/value debate. Sam Harris is one of the most recent controversialists to weigh in on the issue, arguing that "good" means supportive of human well-being and flourishing, which are in turn based on solid facts. "The answer to the question, 'What should I believe, and why should I believe it?' is generally a scientific one..." Brain Science and Human Values

Also: ethical relativism, meta-ethics, and more. And maybe we'll have time to squeeze in consideration of the perennial good-versus-evil trope. Would there be anything "wrong" with a world in which good was already triumphant, happiness for all already secured, kindness and compassion unrivaled by hatred and cruelty? I think it might be just fine. Worth a try, anyway. Where can I vote for that?

==

Boethius (LH); Consolation of Philosophy Bk V (* below); LISTEN: Religious freedom as constraint (HI) and IOT [this is a late addition, not required but strongly recommended]; WATCH: Boethius & Philosophy... dawn post: Boethius... **Anselm & Aquinas (LH); WATCH: Aquinas & 1st Cause (HI) LISTEN:Anthony Kenny on Aquinas' Ethics (PB)....Podcast

1. Who consoles Boethius in his prison cell but also reprimands him for having forgotten her?

2. What paradox puzzles and perplexes Boethius?

3. Why does "Philosophy" say divine foreknowledge does not rob us of free will?

4. Why did Anselm conclude that God must exist?

5. Why did Aquinas think there couldn't be an infinite regress of causes?

6. Is "Nothing" obviously the best answer to "What caused the cosmos?

DQ

- How hard would you find it to take consolation from Philosophy, if you were awaiting your execution? Do you think you could become more "mindful" and less fearful, by studying and reflecting philosophically on the vicissitudes and randomness of "fortune"?

- Comment: "Luck is the residue of design." (Branch Rickey) Can you improve your luck? Why do some succeed and others fail in life? Is it all luck?

- Is the Christian God similar enough to the Platonic form of the Good that a Platonist should be a Christian, or vice versa? Do both offer the same sort of "consolation"? Would Boethius's "Philosophy" be better named "Theodicy"? What's the difference between philosophical consolation and theological justification?

- Do you agree that divine foreknowlege and human free will are not mutually contradictory "if you believe that God is all-knowing?"

- What's your definition of free will? Even if you could not have acted otherwise, in any particular situation, are you still "free" just because you did not know that?

- Why do you think Boethius wrote Consolation of Philosophy as an imagined dialogue, instead of a soliloquy?

- Do you think not existing is an imperfection? What, exactly, is made less perfect by its failure to actually exist? Can we think our way to an understanding of what must be real, and what is merely imaginary?

- Can you infer from a (hypothetically-) necessary First Cause to an omnipotent, omniscient, omni-benevolent God? Can you rule out the possibility that a First Cause might be malevolent or Satanic?

- Bertrand Russell said he gave up belief in God when he encountered J.S. Mill's Autobiography account of not getting a satisfactory answer to the question "What caused God?" Is that a good question, and a good response?

- And there was this great question from Zach: "What would you miss most, in solitary confinement?" People, things, things that give you virtual contact with people...?

==

"Boethius in his cell imagined his visitor: Philosophy personified as a tall woman wearing a dress with the letters Pi to Theta on it. She berates him for deserting her and the stoicism she preached. Boethius’s own book was a response to her challenge..." (from Nigel's essay "Philosophy Should Be Conversation")==

==

COLLEGE students tell me they know how to look someone in the eye and type on their phones at the same time, their split attention undetected. They say it’s a skill they mastered in middle school when they wanted to text in class without getting caught. Now they use it when they want to be both with their friends and, as some put it, “elsewhere.” These days, we feel less of a need to hide the fact that we are dividing our attention. In a 2015 study by the Pew Research Center, 89 percent of cellphone owners said they had used their phones during the last social gathering they attended. But they weren’t happy about it; 82 percent of adults felt that the way they used their phones in social settings hurt the conversation.I’ve been studying the psychology of online connectivity for more than 30 years. For the past five, I’ve had a special focus: What has happened to face-to-face conversation in a world where so many people say they would rather text than talk? I’ve looked at families, friendships and romance. I’ve studied schools, universities and workplaces. When college students explain to me how dividing their attention plays out in the dining hall, some refer to a “rule of three.” In a conversation among five or six people at dinner, you have to check that three people are paying attention — heads up — before you give yourself permission to look down at your phone. So conversation proceeds, but with different people having their heads up at different times. The effect is what you would expect: Conversation is kept relatively light, on topics where people feel they can drop in and out... (from Sherry Terkle's "Stop Googling. Let's Talk")

==

Sherry Turkle is a singular voice in the discourse about technology. She’s a skeptic who was once a believer, a clinical psychologist among the industry shills and the literary hand-wringers, an empiricist among the cherry-picking anecdotalists, a moderate among the extremists, a realist among the fantasists, a humanist but not a Luddite: a grown-up. She holds an endowed chair at M.I.T. and is on close collegial terms with the roboticists and affective-computing engineers who work there. Unlike Jaron Lanier, who bears the stodgy weight of being a Microsoft guy, or Evgeny Morozov, whose perspective is Belarussian, Turkle is a trusted and respected insider. As such, she serves as a kind of conscience for the tech world.

Turkle’s previous book, “Alone Together,” was a damning report on human relationships in the digital age. By observing people’s interactions with robots, and by interviewing them about their computers and phones, she charted the ways in which new technologies render older values obsolete. When we replace human caregivers with robots, or talking with texting, we begin by arguing that the replacements are “better than nothing” but end up considering them “better than anything” — cleaner, less risky, less demanding. Paralleling this shift is a growing preference for the virtual over the real. Robots don’t care about people, but Turkle’s subjects were shockingly quick to settle for the feeling of being cared for and, similarly, to prefer the sense of community that social media deliver, because it comes without the hazards and commitments of a real-world community. In her interviews, again and again, Turkle observed a deep disappointment with human beings, who are flawed and forgetful, needy and unpredictable, in ways that machines are wired not to be. Her new book, “Reclaiming Conversation,” extends her critique, with less emphasis on robots and more on the dissatisfaction with technology reported by her recent interview subjects. She takes their dissatisfaction as a hopeful sign, and her book is straightforwardly a call to arms: Our rapturous submission to digital technology has led to an atrophying of human capacities like empathy and self-reflection, and the time has come to reassert ourselves, behave like adults and put technology in its place... (Jonathan Franzen review of Reclaiming Conversation, continues)

A follow-up from Sherry Turkle on the lost art of conversation:

My recent Sunday Review essay, adapted from my book “Reclaiming Conversation,” made a case for face-to-face talk. The piece argued that direct engagement is crucial for the development of empathy, the ability to put ourselves in the place of others. The article went on to say that it is time to make room for this most basic interaction by first accepting our vulnerability to the constant hum of online connection and then designing our lives and our products to protect against it.==

Some readers agreed with me. Others, even as they disagreed, captured the fragility of conversation today... (continues)

Though one goal of visiting a professor during office hours is certainly transactional — to increase your knowledge and improve your grade — the other is to visit someone who is making an effort to understand you and how you think. And a visit to a professor holds the possibility of giving a student the feeling of adult support and commitment.

But students say they don’t come to office hours because they are afraid of being too dull. They tell me they prefer to email professors because only with the time delay and the possibility of editing can they best explain their work. My students suggest that an email from them will put me in the best position to improve their ideas. They cast our meeting in purely transactional terms, judging that the online transaction will yield better results than a face-to-face meeting.

Zvi, a college junior who doesn’t like to see his professors in person but prefers to email, used transactional language to describe what he might get out of office hours: He has ideas; the professors have information that will improve them. In the end, Zvi walked back his position and admitted that he stays away from professors because he doesn’t feel grown-up enough to talk to them. His professors might be able to help him with this, but not because they’ll give him information.

Studies of mentoring show that what makes a difference, what can change the life of a student, is the presence of a strong figure who shows an interest, who, as a student might say, “gets me.”

You need face-to-face conversation for that. nyt

*From Consolation of Philosophy, Book V-'Since, then, as we lately proved, everything that is known is cognized not in accordance with its own nature, but in accordance with the nature of the faculty that comprehends it, let us now contemplate, as far as lawful, the character of the Divine essence, that we may be able to understand also the nature of its knowledge.

'God is eternal; in this judgment all rational beings agree. Let us, then, consider what eternity is. For this word carries with it a revelation alike of the Divine nature and of the Divine knowledge. Now, eternity is the possession of endless life whole and perfect at a single moment. What this is becomes more clear and manifest from a comparison with things temporal. For whatever lives in time is a present proceeding from the past to the future, and there is nothing set in time which can embrace the whole space of its life together. To-morrow's state it grasps not yet, while it has already lost yesterday's; nay, even in the life of to-day ye live no longer than one brief transitory moment. Whatever, therefore, is subject to the condition of time, although, as Aristotle deemed of the world, it never have either beginning or end, and its life be stretched to the whole extent of time's infinity, it yet is not such as rightly to be thought eternal. For it does not include and embrace the whole space of infinite life at once, but has no present hold on things to come, not yet accomplished. Accordingly, that which includes and possesses the whole fulness of unending life at once, from which nothing future is absent, from which nothing past has escaped, this is rightly called eternal; this must of necessity be ever present to itself in full self-possession, and hold the infinity of movable time in an abiding present. Wherefore they deem not rightly who imagine that on Plato's principles the created world is made co-eternal with the Creator, because they are told that hebelieved the world to have had no beginning in time,[S] and to be destined never to come to an end. For it is one thing for existence to be endlessly prolonged, which was what Plato ascribed to the world, another for the whole of an endless life to be embraced in the present, which is manifestly a property peculiar to the Divine mind. Nor need God appear earlier in mere duration of time to created things, but only prior in the unique simplicity of His nature. For the infinite progression of things in time copies this immediate existence in the present of the changeless life, and when it cannot succeed in equalling it, declines from movelessness into motion, and falls away from the simplicity of a perpetual present to the infinite duration of the future and the past; and since it cannot possess the whole fulness of its life together, for the very reason that in a manner it never ceases to be, it seems, up to a certain point, to rival that which it cannot complete and express by attaching itself indifferently to any present moment of time, however swift and brief; and since this bears some resemblance to that ever-abiding present, it bestows on everything to which it is assigned the semblance of existence. But since it cannot abide, it hurries along the infinite path of time, and the result has been that it continues by ceaseless movement the life the completeness of which it could not embrace while it stood still. So, if we are minded to give things their right names, we shall follow Plato in saying that God indeed is eternal, but the world everlasting.

'Since, then, every mode of judgment comprehends its objects conformably to its own nature, and since God abides for ever in an eternal present, His knowledge, also transcending all movement of time, dwells in the simplicity of its own changeless present, and, embracing the whole infinite sweep of the past and of the future, contemplates all that falls within its simple cognition as if it were now taking place. And therefore, if thou wilt carefully consider that immediate presentment whereby it discriminates all things, thou wilt more rightly deem it not foreknowledge as of something future, but knowledge of a moment that never passes. For this cause the name chosen to describe it is not prevision, but providence, because, since utterly removed in nature from things mean and trivial, its outlook embraces all things as from some lofty height. Why, then, dost thou insist that the things which are surveyed by the Divine eye are involved in necessity, whereas clearly men impose no necessity on things which they see? Does the act of vision add any necessity to the things which thou seest before thy eyes?'

'Assuredly not.'

And yet, if we may without unfitness compare God's present and man's, just as ye see certain things in this your temporary present, so does He see all things in His eternal present. Wherefore this Divine anticipation changes not the natures and properties of things, and it beholds things present before it, just as they will hereafter come to pass in time. Nor does it confound things in its judgment, but in the one mental view distinguishes alike what will come necessarily and what without necessity. For even as ye, when at one and the same time ye see a man walking on the earth and the sun rising in the sky, distinguish between the two, though one glance embraces both, and judge the former voluntary, the latter necessary action: so also the Divine vision in its universal range of view does in no wise confuse the characters of the things which are present to its regard, though future in respect of time. Whence it follows that when it perceives that something will come into existence, and yet is perfectly aware that this is unbound by any necessity, its apprehension is not opinion, but rather knowledge based on truth. And if to this thou sayest that what God sees to be about to come to pass cannot fail to come to pass, and that what cannot fail to come to pass happens of necessity, and wilt tie me down to this word necessity, I will acknowledge that thou affirmest a most solid truth, but one which scarcely anyone can approach to who has not made theDivine his special study. For my answer would be that the same future event is necessary from the standpoint of Divine knowledge, but when considered in its own nature it seems absolutely free and unfettered. So, then, there are two necessities—one simple, as that men are necessarily mortal; the other conditioned, as that, if you know that someone is walking, he must necessarily be walking. For that which is known cannot indeed be otherwise than as it is known to be, and yet this fact by no means carries with it that other simple necessity. For the former necessity is not imposed by the thing's own proper nature, but by the addition of a condition. No necessity compels one who is voluntarily walking to go forward, although it is necessary for him to go forward at the moment of walking. In the same way, then, if Providence sees anything as present, that must necessarily be, though it is bound by no necessity of nature. Now, God views as present those coming events which happen of free will. These, accordingly, from the standpoint of the Divine vision are made necessary conditionally on the Divine cognizance; viewed, however, in themselves, they desist not from the absolute freedom naturally theirs. Accordingly, without doubt, all things will come to pass which God foreknows as about to happen, but of these certain proceed of free will; and though these happen, yet by the fact of their existence they do not lose their proper nature, in virtue of which before they happened it was really possible that they might not have come to pass.

'What difference, then, does the denial of necessity make, since, through their being conditioned by Divine knowledge, they come to pass as if they were in all respects under the compulsion of necessity? This difference, surely, which we saw in the case of the instances I formerly took, the sun's rising and the man's walking; which at the moment of their occurrence could not but be taking place, and yet one of them before it took place was necessarily obliged to be, while the other was not so at all. So likewise the things which to God are present without doubt exist, but some of them come from the necessity of things, others from the power of the agent. Quite rightly, then, have we said that these things are necessary if viewed from the standpoint of the Divine knowledge; but if they are considered in themselves, they are free from the bonds of necessity, even as everything which is accessible to sense, regarded from the standpoint of Thought, is universal, but viewed in its own nature particular. "But," thou wilt say, "if it is in my power to change my purpose, I shall make void providence, since I shall perchance change something which comes within its foreknowledge." My answer is: Thou canst indeed turn aside thy purpose; but since the truth of providence is ever at hand to see that thou canst, and whether thou dost, and whither thou turnest thyself, thou canst not avoid the Divine foreknowledge, even as thou canst not escape the sight of a present spectator, although of thy free will thou turn thyself to various actions. Wilt thou, then, say: "Shall the Divine knowledge be changed at my discretion, so that, when I will this or that, providence changes its knowledge correspondingly?"

'Surely not.'

'True, for the Divine vision anticipates all that is coming, and transforms and reduces it to the form of its own present knowledge, and varies not, as thou deemest, in its foreknowledge, alternating to this or that, but in a single flash it forestalls and includes thy mutations without altering. And this ever-present comprehension and survey of all things God has received, not from the issue of future events, but from the simplicity of His own nature. Hereby also is resolved the objection which a little while ago gave thee offence—that our doings in the future were spoken of as if supplying the cause of God's knowledge. For this faculty of knowledge, embracing all things in its immediate cognizance, has itself fixed the bounds of all things, yet itself owes nothing to what comes after.

'And all this being so, the freedom of man's will stands unshaken, and laws are not unrighteous, since their rewards and punishments are held forth to wills unbound by any necessity. God, who foreknoweth all things, still looks down from above, and the ever-present eternity of His vision concurs with the future character of all our acts, and dispenseth to the good rewards, to the bad punishments. Our hopes and prayers also are not fixed on God in vain, and when they are rightly directed cannot fail of effect. Therefore, withstand vice, practise virtue, lift up your souls to right hopes, offer humble prayers to Heaven. Great is the necessity of righteousness laid upon you if ye will not hide it from yourselves, seeing that all your actions are done before the eyes of a Judge who seeth all things.'

EPILOGUE. Within a short time of writing 'The Consolation of Philosophy,' Boethius died by a cruel death. As to the manner of his death there is some uncertainty. According to one account, he was cut down by the swords of the soldiers before the very judgment-seat of Theodoric; according to another, a cord was first fastened round his forehead, and tightened till 'his eyes started'; he was then killed with a club.

==

An old post

Tuesday, February 17, 2015

Boethius & Bentham & animal rights

Today in CoPhi it's the pagan/stoic/Christian/Platonist martyr Boethius, and then the rights of animals.

We saw last time that Bertrand Russell had little regard for how Augustine, despite his philosophical sophistication when it came to hard-nut conceptual problems like time, ironically squandered much of his own on a preoccupation with sin, chastity, and staying out of hell.

Russell liked Boethius, or aspects of his thought at least. Boethius was also perplexed by time, and initially unimpressed by the alleged capacity of timeless divinity to accommodate both omniscience and free will. Like Russell, I'm struck by this "singular" thinker's ability to contemplate happiness (he thought all genuinely happy people are gods) while practically darkening death's door.

Boethius was consoled by the thought that God’s foreknowledge of everything, including the fact that Boethius himself (among too many others) would be unjustly imprisoned and tortured to death, in no way impaired his (Boethius’s) freedom or god's perfection. Consoled. Comforted.Calmed. Reconciled.

That’s apparently because God knows things timelessly, sees everything “in a go.” I don’t think that would really make me feel any better, in my prison cell. The real consolation of philosophycomes when it contributes to the liberation of mind and body (one thing, not two). But it’s still very cool to imagine Philosophy a comfort-woman, reminding us of our hard-earned wisdom when the going gets impossible.

And then, of course, they killed him. The list of martyred philosophers grows. And let’s not forgetHypatia and Bruno. [Russell] The problem of suffering (“evil”) was very real to them, as it is to so many of our fellow world-citizens. You can’t chalk it all up to free will. But can we even chalk torture or any other inflicted choice up to it, given the full scope of a genuinely omniscient creator’s knowledge? If He already knows what I’m going to do unto others and what others will do unto me, am I in any meaningful sense a free agent who might have done otherwise? The buck stops where?

For those keeping score, add Boethius to Aristotle's column.

[Christians 2, Philosophers 0... Christians & Muslims...JandMoandPaul...Mystics, scholastics, Ferengi... faith & reason...]

(H3)Russel on Augustine? I have to agree with Russel on this one. I think, likely to some sense of guilt or insufficiency, he dwelled on his own sin and sin in general too much, trying to fine an answer to the question of sin and Gods position on the sins of man. Which inevitably brought him to hi rather pessimistic outlook on sin and Final Judgment.

ReplyDeleteI agree, i think Augustine spent more time on sin than needed because it turned his view of humanity to a negative light overall.

Delete(H3) sin and God? I would say yes sin and moral evil can explain it at least to some extent. Although the explanation only holds up if you assume that human being have already been so through with their sinning and shortcomings that if we were fully aware of them that we would convict ourselves even for our sin, and so God is justified in doing so There for the amount of grace and mercy he has already shown to us in sending Christ to redeem us among other things is a sign that he ha hown us far more leniency than we deserve.

ReplyDelete(H3) free will and hurricanes? No, I do not believe that free will in anyway explains natural disasters unless you accept them as punishment sent by some higher power for actions taken as the result of free will.

ReplyDeleteFree will might actually have some affect on natural disasters however. The way humans use the material we have and release all sorts of toxins in the environment, some natural disasters could very will be from what we have done with our free will.

DeleteI agree with you Sean. I think humans and our lack of regard for the environment effects the frequency and severity of these events.

Delete(H3) Are infants full of sin? That is a question I cannot answer philosophically and must answer theosophically. Yes, they are full of sin, as they still commit acts, that, if performed by an adult would be considered a sin. Whether they know what they are doing or not does not change what they are doing. Do I think that all unbaptized infants are damned to eternal torment? That I cannot answer.

ReplyDelete(h3) God, creation, time? I personally think it does my theology aside I never really found myself able to believe that everything ha and always will be. To me all that does exist must have not at some time. Conventional science offers an answer and that answer ha the same caveat attached to it, unless, that is, there was some kind of intelligent design. When it comes to time I must ask that, even if time did exist before everything else. What meaning does time have in a world of nothing, no light, no dark, no up or down or left or right?

ReplyDeleteI agree in that everything that exists must not have existed. However, that is something we most likely will never be able to answer. There is no way to fully understand the 'creation' if there was a creation and there is no way to understand what came before time if it didn't exist at some point.

Delete(H3) Consolation of Philosophy: Perhaps because he intended it to be a work of philosophy?

ReplyDelete(H3) solitude? I do enjoy a good bout of solitary confinement. Being alone is very beneficial to my thought process sometimes.

ReplyDeleteToo much solitude can be unnerving though. It can lead to depression or even a feeling of complete isolation if we are alone too much.

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete(H3) me my body and I? yes they undoubtedly argue and debate because we all have inner and outer motivations and conflicts.

ReplyDeleteH1

DeleteI do feel the body and I debates, usually on the subject of whether I should be eating all this candy or not. Oddly enough, my body seems to be more in control of some of my actions than my mind is :)

(H3)silence or noise? I do enjoy silence but I think that human being are just programed to dislike the absence of noise. If we were in nature, there could always be noise, if we are in a town or city, there is always noise. The complete lack of noise is unnerving and unnatural.

ReplyDelete(H3) Does free will explain suffering due to natural phenomena? It does not, the two are mutually exclusive. Like Bryce commented, unless you take them as signs, natural phenomenon are just that: natural and scientifically explained. Disasters such as earthquakes and hurricanes are tragedies, not punishments.

ReplyDeleteH1

DeleteThat's really well put. I agree. I think having a fire burn your house or being born with a genetic medical condition (and the like), are not reflections on your or your parent's righteousness; natural phenomena aren't punishments.

Well you also have to consider the damage that humans do to the environment. Some natural disasters can be directly related to the toxins that we pour daily into the world around us. Genetic medical conditions can be directly connected to radiation in which humans have created by splitting atoms. However, most natural disasters have nothing to do with our free will. We just have to consider the few that are directly related.

Delete(H3) Do I enjoy silence? Definitely not. Having some sort of background noise helps me be in control of my surroundings. When everything is silent, it's so loud that's all I can focus on.

ReplyDeleteBeing wordless without any internal narration just reminds me of 'mental numbness', and being ceaseless in thought does not create growth or any kind of perceived higher thought from silence.

I like the way you worded that. "When everything is silent, it's so loud.." It seems like an impossible statement, unless you've experienced it.

Delete(H3) Are infants full of sin?

ReplyDeleteInfants, like adults, have the nature of sin, but they can barely preform any kind of extreme sin, much less understand the difference between right and wrong. Therefore I would say they are not "full of sin", but instead they have the capability to sin but are not able to be held accountable for their actions at such a young age.

H1

DeleteI agree; total innocence and ignorance make them unaccountable; the sins they are capable are much more innocent as well.

I don't think infants are full of sin because they simply are innocent. Their minds have not discovered what sin is and cannot make the choice to be sinful or not. Performing a sin to me is knowing that it is a sin but still doing it because of personal enjoyment. Infants aren't capable of knowing what a sin is so infants cannot be full of sin.

Delete(H1) Do you enjoy solitude and alone-time? Or do you hate being by yourself?

ReplyDeleteA certain amount of time should be allotted for both solitude and time with others. When alone, one feels more free to act naturally and behave how they wish rather than possibly putting on a sort of "act" in front of others whether they are aware of it or not. It allows one to think their own thoughts and dedicate time to what they think is important. Conversely, spending time with others allows for discussion and the chance to preview your ideas to a small audience and get feedback. It allows you to see things from others' perspectives and get insight into new ideas.

H1

DeleteI really like that. You hit a great point about balance; humans are social animals that also really need to have time to themselves; privacy of the mind and privacy of the action. Having an even mixture of those two things helps us stay as honest and as real with ourselves as we can get.

(H1) Do you find the concept of Original Sin compelling, difficult, unfair, or dubious? In general, do we "inherit the sins of our fathers (and mothers)"? If yes, give examples and explain.

ReplyDeleteThe idea that we inherit sin is hardly fair and removes any fighting chance we may have as to the fate of our immortal souls. Each person must account for their own transgressions as those are their own mistakes, produced by circumstance that they alone found themselves in. It is only human nature to sin and to expect otherwise is ridiculous. The amount of sin each person may commit may be different but we all sin in some way and if this must be combined with the sins of our fathers then what is the point in even trying to be good when you never had a chance?

(H3) I do agree that Augustine's extreme sense of sin made him and his philosophy stern and inhuman. I think his self-deprecating demeanor made him hate the bad parts of himself and therefore he developed a philosophy concerned with the irradication of sin. Since humans are not perfect or without sin, his philosophy is not realistic or held to higher standard than humans are capable.

ReplyDelete(H3) I do not agree that even infants are born full of sin. I believe we are born a blank slate and that our environment, experiences, and free will govern who we become. Bad people aren't born bad, that's a worthless excuse in my opinion. We each have a choice in our actions, maybe our upbringing and past experiences influence our decision-making but in the end it is still that person's choice to commit a sin/crime.

ReplyDelete(H3) I don't think it solves the mystery of existence to say that time and space were created when the world was created, that God preceded both. It makes me question who or what created God. Something had to cause this initial event/existence. It's hard to believe that one entity the just appeared out of nowhere. I like to believe in a cause-and- effect equation. In this scenario, we are missing a vital part of the equation, the cause.

ReplyDeleteAgreed. I personally do not know what came first, but something must and i akways wonder why that thing came first and what made it come. According to many, there is just spontaneous existence and i refuse to accept that.

Delete(H3) I truly enjoy being alone. I'm an only child and have spent most of my life moving around with the military. Though I was good at making friends, I like hanging out alone as well, it was a constant and one that I was good at. I think being able to enjoy solitude is a healthy part of life. Don't get me wrong, talking and conversing with other people is great; we are social by nature. However, a little peace and quiet never did anyone any harm.

ReplyDeleteH1

ReplyDeleteDQ •Do you enjoy solitude and alone-time? Or do you hate being by yourself?

I love solitude and alone time; its rejuvenating and mind-clearing. I like what Gros wrote about it; when walking alone through nature, it's the best possible combination of solitude and company. I think everybody should do this. However, I do think there are probably some exceptions; strong extraverts probably won't get as much out of the experience, but I think they should experience it several times at least.

H1

ReplyDelete• Do you ever converse with yourself? Is it a dialogue between body and soul, between different aspects of your self, or what?

Yes, I often do. I'll debate a moral issue with myself, make plans for the day, or imagine interactions between characters that I'm writing about, acting out the parts in my head. Usually this conversation is between different aspects of myself.

H1

ReplyDeleteDQ: Do you agree that divine foreknowlege and human free will are not mutually contradictory "if you believe that God is all-knowing?"

Yes I do. If I know that you'll love cookies my mom made, and that you'll eat more than three, that does not interfere with your independence at all. My knowledge is not forcing you to make certain actions.

H1

ReplyDeleteDQ:Do you enjoy silence, or must you fill every moment with chatter, music, background noise, etc.? Do you ever try to just be, wordlessly, without internal narration or commentary?

I should do this so much more. I have been silent, while walking or simply at my apartment. It's a fascinating experience, which is unexpected. Usually I read, or study, or listen to podcasts or music, or work, or spend time with my friends and family. All of these activities are important, but I always cut my alone time with my mind short.

H1

ReplyDeleteDQ: •What's your definition of free will? Even if you could not have acted otherwise, in any particular situation, are you still "free" just because you did not know that?

I think that free will is the ability to make choices. These can be influenced, especially by life circumstances and disposition, obviously, but I believe that I'm in charge of my actions. I can reduce my free will, but only through previous actions; addiction takes away a lot of free will, but choosing to take heroin or meth is a choice.

I agree. We all have free will. No matter what happens to us, we will always have a choice in what we do meaning that our will will always be ours and it will always be free.

DeleteI agree as well. Our default mode is being of free will. I wonder though, would you consider someone responsible for actions they make based on limited choice or outside pressure?

DeleteEven with limited choice or outside pressure, you should always take responsibility for the consequence of your actions, whether that is making up for a mistake or living with your decision. I would never blame or judge that person. I don't think responsible necessarily means having punishment

DeleteInfants being full of sin can only be answered in a theological sense. Philosophy cannot really take hold of this question because sin comes from the idea of religion and the guidelines to a moral life that some God has set down.

ReplyDeletePersonally, i love solittude and alone time. It gives me time to think without any distractions and with noone around to influence my thinking.

ReplyDeleteI enjoy silence. It helps me bring peace to my mind. The only exception to that is when i am in the natural world. When i am immersed in nature i find i enjoy the sounds much more than any silence and that the natural sounds bring more peace to my mind than silence.

ReplyDeleteI love nature sounds as well. It's peaceful and brings my mind ease. I actually go to sleep listening to sounds of nature.

DeleteI converse with myself all the time. Never out loud though, always secluded in my own mind. I enjoy doing this also because i can debate issues with myself bringing up all the pros and cons without outside influence so i can make decisions for myself.

ReplyDeleteDQ: Do you think Augustine's obsession with sin only existed as a result of his spotted past? Might he have held more charitable views of mankind if he had not been experiencing what can only be described as ferocious guilt?

ReplyDeleteDo I enjoy solitude? The general pattern in my life is needing 6 days of the week full of people and 1 day to myself.

ReplyDeleteYes, I like silence, and also white noise. As for background music, no such thing for me. If music is playing, it immediately steals my attention from whatever else I'm supposed to be doing; the only exception being when I am talking with someone.