LISTEN (But, CORRECTION: it was Augustine, not Boethius, who converted to Christianity from Manichaeanism. I inadvertently misspoke, discussing #1 below. Also NOTE: Boethius, nominally Christian, always retained a strong commitment to Stoicism (hence his famous work Consolation of Philosophy)... and the answer to #2 is that in that work he does not mention his own commitment to Christianity.

Post your comments etc., keep a detailed and itemized list of everything you post, and include that list in your last post this week. Remember, you need 4 bases to earn a participation run... and your goal is to earn a run for each scheduled class.

LH

Post your comments etc., keep a detailed and itemized list of everything you post, and include that list in your last post this week. Remember, you need 4 bases to earn a participation run... and your goal is to earn a run for each scheduled class.

LH

1. How did Augustine "solve" the problem of evil in his younger days, and then after his conversion to Christianity? Why wasn't it such a problem for him originally?

2. What does Boethius not mention about himself in The Consolation of Philosophy?

3. Boethius' "recollection of ideas" can be traced back to what philosopher?

4. What uniquely self-validating idea did Anselm say we have?

5. Gaunilo criticized Anselm's reasoning using what example?

6. What was Aquinas' 2nd Way?

FL

9. By the end of the '50s how much TV did the average American watch?

10. Who was the Steve Jobs of his era?

11. Of what was Disneyland "more or less a replica"?

12. What fantasy did Hugh Hefner promote?

13. Who was our "ad hoc national Pastor-in-Chief"?

14. In the second year of Eisenhower's presidency (1954), what was inserted into the Pledge of Allegiance?

Discussion Questions

DQ

- Add yours

- Which is more plausible, that God exists but is not more powerful than Satan, or that neither God nor Satan exists? Why?

- Are supernatural stories of faith, redemption, and salvation more comforting to you than the power of reason and evidence?

- What do you think of the Manichean idea that an "evil God created the earth and emtombed our souls in the prisons of our bodies"? 392

- Do you agree with Augustine about "the main message of Christianity"? 395 If not, what do you think the message is?

- What do you think of Boethius' solution to the puzzle of free will? 402

- Did Russell "demolish" Anselm's ontological argument? (See below)

- COMMENT: “The world is so exquisite with so much love and moral depth, that there is no reason to deceive ourselves with pretty stories for which there's little good evidence. Far better it seems to me, in our vulnerability, is to look death in the eye and to be grateful every day for the brief but magnificent opportunity that life provides.”

- COMMENT: “Science is not only compatible with spirituality; it is a profound source of spirituality. When we recognize our place in an immensity of light‐years and in the passage of ages, when we grasp the intricacy, beauty, and subtlety of life, then that soaring feeling, that sense of elation and humility combined, is surely spiritual. So are our emotions in the presence of great art or music or literature, or acts of exemplary selfless courage such as those of Mohandas Gandhi or Martin Luther King, Jr. The notion that science and spirituality are somehow mutually exclusive does a disservice to both.” Carl Sagan

- If you were falsely imprisoned, tortured, and scheduled for execution, would you be able to achieve "consolation"? How?

- Can the definition of a word prove anything about the world?

- Is theoretical simplicity always better, even if the universe is complex?

- Does the possibility of other worlds somehow diminish humanity?

- How does the definition of God as omniscient, omnipotent, and perfectly good make it harder to account for evil and suffering in the world? Would it be better to believe in a lesser god, or no god at all?

- Can you explain the concept of Original Sin? Do you think you understand it?

- Is it better to embrace (or renounce) religious faith early in life, or to "sow your wild oats" and enjoy a wide experience of the world before committing to any particular tradition or belief? Were you encouraged by adults, in childhood, to make a public profession of faith? If so, did you understand what that meant or entailed?

- Does the concept of a never-ending struggle between good and evil appeal to you? Does it make sense, in the light of whatever else you believe? Would there be anything "wrong" with a world in which good was already triumphant, happiness for all already secured, kindness and compassion unrivaled by hatred and cruelty?

- Do you find the concept of Original Sin compelling, difficult, unfair, or dubious? In general, do we "inherit the sins of our fathers (and mothers)"? If yes, give examples and explain.

- What kinds of present-day McCarthyism can you see? Is socialism the new communism? How are alternate political philosophies discouraged in America, and where would you place yourself on the spectrum?

- Andersen notes that since WWII "mainline" Christian denominations were peaking (and, as evidence shows, are now declining). What do you think about this when you consider the visible political power of other evangelical denominations? Are you a part of a mainline traditon? If so, how would you explain this shift?

from Russell's History-

...Saint Augustine taught that Adam, before the Fall, had had free will, and could have abstained from sin. But as he and Eve ate the apple, corruption entered into them, and descended to all their posterity, none of whom can, of their own power, abstain from sin. Only God's grace enables men to be virtuous. Since we all inherit Adam's sin, we all deserve eternal damnation. All who die unbaptized, even infants, will go to hell and suffer unending torment. We have no reason to complain of this, since we are all wicked. (In the Confessions, the Saint enumerates the crimes of which he was guilty in the cradle.) But by God's free grace certain people, among those who have been baptized, are chosen to go to heaven; these are the elect. They do not go to heaven because they are good; we are all totally depraved, except in so far as God's grace, which is only bestowed on the elect, enables us to be otherwise. No reason can be given why some are saved and the rest damned; this is due to God's unmotived choice. Damnation proves God's justice; salvation His mercy. Both equally display His goodness. The arguments in favour of this ferocious doctrine--which was revived by Calvin, and has since then not been held by the Catholic Church--are to be found in the writings of Saint Paul, particularly the Epistle to the Romans. These are treated by Augustine as a lawyer treats the law: the interpretation is able, and the texts are made to yield their utmost meaning. One is persuaded, at the end, not that Saint Paul believed what Augustine deduces, but that, taking certain texts in isolation, they do imply just what he says they do. It may seem odd that the damnation of unbaptized infants should not have been thought shocking, but should have been attributed to a good God. The conviction of sin, however, so dominated him that he really believed new-born children to be limbs of Satan. A great deal of what is most ferocious in the medieval Church is traceable to his gloomy sense of universal guilt. There is only one intellectual difficulty that really troubles Saint Augustine. This is not that it seems a pity to have created Man, since the immense majority of the human race are predestined to eternal torment. What troubles him is that, if original sin is inherited from Adam, as Saint Paul teaches, the soul, as well as the body, must be -365- propagated by the parents, for sin is of the soul, not the body. He sees difficulties in this doctrine, but says that, since Scripture is silent, it cannot be necessary to salvation to arrive at a just view on the matter. He therefore leaves it undecided. It is strange that the last men of intellectual eminence before the dark ages were concerned, not with saving civilization or expelling the barbarians or reforming the abuses of the administration, but with preaching the merit of virginity and the damnation of unbaptized infants. Seeing that these were the preoccupations that the Church handed on to the converted barbarians, it is no wonder that the succeeding age surpassed almost all other fully historical periods in cruelty and superstition...

...Boethius is a singular figure. Throughout the Middle Ages he was read and admired, regarded always as a devout Christian, and treated almost as if he had been one of the Fathers. Yet his Consolations of Philosophy, written in 524 while he was awaiting execution, is purely Platonic; it does not prove that he was not a Christian, but it does show that pagan philosophy had a much stronger hold on him then Christian theology. Some theological works, especially one on the Trinity, which are attributed to him, are by many authorities considered to be spurious; but it was probably owing to them that the Middle Ages were able to regard him as orthodox, and to imbibe from him much Platonism which would otherwise have been viewed with suspicion. The work is an alternation of verse and prose: Boethius, in his own person, speaks in prose, while Philosophy answers in verse. There is at certain resemblance to Dante, who was no doubt influenced by him in the Vita Nuova. The Consolations, which Gibbon rightly calls a "golden volume," begins by the statement that Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle are the true philosophers; Stoics, Epicureans, and the rest are usurpers, whom the profane multitude mistook for the friends of philosophy. Boethius says he obeyed the Pythagorean command to "follow God" (not the Christian command). Happiness, which is the same thing as blessedness, is the good, not pleasure. Friendship is a "most sacred thing." There is much morality that agrees closely with Stoic doctrine, and is in fact largely taken from Seneca. There is a summary, in verse, of the beginning of the Timaeus. This is followed by a great deal of purely Platonic metaphysics. Imperfection, we are told, is a lack, implying the existence of a perfect pattern. He adopts the privative theory of evil. He then passes on to a pantheism which should have shocked Christians, but for some reason did not. Blessedness and God, he says, are both the chiefest good, and are therefore identical. "Men are made happy by the obtaining of divinity." "They who obtain divinity become gods. Wherefore every one that is happy -370- is a god, but by nature there is only one God, but there may be many by participation." "The sum, origin, and cause of all that is sought after is rightly thought to be goodness." "The substance of God consisteth in nothing else but in goodness." Can God do evil? No. Therefore evil is nothing, since God can do everything. Virtuous men are always powerful, and bad men always weak; for both desire the good, but only the virtuous get it. The wicked are more unfortunate if they escape punishment than if they suffer it. (Note that this could not be said of punishment in hell.) "In wise men there is no place for hatred." The tone of the book is more like that of Plato than that of Plotinus. There is no trace of the superstition or morbidness of the age, no obsession with sin, no excessive straining after the unattainable. There is perfect philosophic calm--so much that, if the book had been written in prosperity, it might almost have been called smug. Written when it was, in prison under sentence of death, it is as admirable as the last moments of the Platonic Socrates. One does not find a similar outlook until after Newton. I will quote in extenso one poem from the book, which, in its philosophy, is not unlike Pope Essay on Man. If Thou wouldst see God's laws with purest mind, Thy sight on heaven must fixed be, Whose settled course the stars in peace doth bind. The sun's bright fire Stops not his sister's team, Nor doth the northern bear desire Within the ocean's wave to hide her beam. Though she behold The other stars there couching, Yet she incessantly is rolled About high heaven, the ocean never touching. The evening light With certain course doth show The coming of the shady night, And Lucifer before the day doth go. This mutual love Courses eternal makes, -371- And from the starry spheres above All cause of war and dangerous discord takes. This sweet consent In equal bands doth tie The nature of each element So that the moist things yield unto the dry. The piercing cold With flames doth friendship heap The trembling fire the highest place doth hold, And the gross earth sinks down into the deep. The flowery year Breathes odours in the spring, The scorching summer corn doth bear The autumn fruit from laden trees doth bring. The falling rain Doth winter's moisture give. These rules thus nourish and maintain All creatures which we see on earth to live. And when they die, These bring them to their end, While their Creator sits on high, Whose hand the reins of the whole world doth bend. He as their king Rules them with lordly might. From Him they rise, flourish, and spring, He as their law and judge decides their right. Those things whose course Most swiftly glides away His might doth often backward force, And suddenly their wandering motion stay. Unless his strength Their violence should bound, And them which else would run at length, Should bring within the compass of a round, That firm decree Which now doth all adorn Would soon destroyed and broken be, Things being far from their beginning borne. This powerful love Is common unto all. -372- Which for desire of good do move Back to the springs from whence they first did fall. No worldly thing Can a continuance have Unless love back again it bring Unto the cause which first the essence gave. Boethius was, until the end, a friend of Theodoric. His father was consul, he was consul, and so were his two sons. His father-in-law Symmachus (probably grandson of the one who had a controversy with Ambrose about the statue of Victory) was an important man in the court of the Gothic king. Theodoric employed Boethius to reform the coinage, and to astonish less sophisticated barbarian kings with such devices as sun-dials and water-clocks. It may be that his freedom from superstition was not so exceptional in Roman aristocratic families as elsewhere; but its combination with great learning and zeal for the public good was unique in that age. During the two centuries before his time and the ten centuries after it, I cannot think of any European man of learning so free from superstition and fanaticism. Nor are his merits merely negative; his survey is lofty, disinterested, and sublime. He would have been remarkable in any age; in the age in which he lived, he is utterly amazing. The medieval reputation of Boethius was partly due to his being regarded as a martyr to Arian persecution--a view which began two or three hundred years after his death. In Pavia, he was regarded as a saint, but in fact he was not canonized. Though Cyril was a saint, Boethius was not. Two years after the execution of Boethius, Theodoric died. In the next year, Justinian became Emperor. He reigned until 565, and in this long time managed to do much harm and some good. He is of course chiefly famous for his Digest. But I shall not venture on this topic, which is one for the lawyers. He was a man of deep piety, which he signalized, two years after his accession, by closing the schools of philosophy in Athens, where paganism still reigned. The dispossessed philosophers betook themselves to Persia, where the king received them kindly. But they were shocked--more so, says Gibbon, than became philosophers--by the Persian practices of polygamy and incest, so they returned home again, and faded into obscurity...

...Saint Anselm was, like Lanfranc, an Italian, a monk at Bec, and archbishop of Canterbury ( 1093- 1109), in which capacity he followed the principles of Gregory VII and quarrelled with the king. He is chiefly known to fame as the inventor of the "ontological argument" for the existence of God. As he put it, the argument is as follows: We define "God" as the greatest possible object of thought. Now if an object of thought does not exist, another, exactly like it, which does exist, is greater. Therefore the greatest of all objects of thought must exist, since, otherwise, another, still greater, would be possible. Therefore God exists. This argument has never been accepted by theologians. It was adversely criticized at the time; then it was forgotten till the latter half of the thirteenth century. Thomas Aquinas rejected it, and among theologians his authority has prevailed ever since. But among philosophers it has had a better fate. Descartes revived it in a somewhat amended form; Leibniz thought that it could be made valid by the addition of a supplement to prove that God is possible. Kant considered that he had demolished it once for all. Nevertheless, in some sense, it underlies the system of Hegel and his followers, and reappears in Bradley's principle: "What may be and must be, is." Clearly an argument with such a distinguished history is to be treated with respect, whether valid or not. The real question is: Is there anything we can think of which, by the mere fact that we can think of it, is shown to exist outside our thought? Every philosopher would like to say yes, because a philosopher's job is to find out things about the world by thinking rather than observing. If yes is the right answer, there is a bridge from pure thought to things; if not, not. In this generalized form, Plato uses a kind of ontological argument to prove the objective reality of ideas. But no one before Anselm had -417- stated the argument in its naked logical purity. In gaining purity, it loses plausibility; but this also is to Anselm's credit. For the rest, Anselm's philosophy is mainly derived from Saint Augustine, from whom it acquires many Platonic elements. He believes in Platonic ideas, from which he derives another proof of the existence of God. By Neoplatonic arguments he professes to prove not only God, but the Trinity. (It will be remembered that Plotinus has a Trinity, though not one that a Christian can accept as orthodox.) Anselm considers reason subordinate to faith. "I believe in order to understand," he says; following Augustine, he holds that without belief it is impossible to understand. God, he says, is not just, but justice. It will be remembered that John the Scot says similar things. The common origin is in Plato. Saint Anselm, like his predecessors in Christian philosophy, is in the Platonic rather than the Aristotelian tradition. For this reason, he has not the distinctive characteristics of the philosophy which is called "scholastic," which culminated in Thomas Aquinas. This kind of philosophy may be reckoned as beginning with Roscelin, who was Anselm's contemporary, being seventeen years younger than Anselm. Roscelin marks a new beginning, and will be considered in the next chapter. When it is said that medieval philosophy, until the thirteenth century, was mainly Platonic, it must be remembered that Plato, except for a fragment of the Timaeus, was known only at second or third hand. John the Scot, for example, could not have held the views which he did hold but for Plato, but most of what is Platonic in him comes from the pseudo-Dionysius. The date of this author is uncertain, but it seems probable that he was a disciple of Proclus the Neoplatonist. It is probable, also, that John the Scot had never heard of Proclus or read a line of Plotinus. Apart from the pseudo-Dionysius, the other source of Platonism in the Middle Ages was Boethius. This Platonism was in many ways different from that which a modern student derives from Plato's own writings. It omitted almost everything that had no obvious bearing on religion, and in religious philosophy it enlarged and emphasized certain aspects at the expense of others. This change in the conception of Plato had already been effected by Plotinus. The knowledge of Aristotle was also fragmentary, but in an opposite direction: all that was known of him until the twelfth -418- century was Boethius translation of the Categories and De Emendatione. Thus Aristotle was conceived as a mere dialectician, and Plato as only a religious philosopher and the author of the theory of ideas. During the course of the later Middle Ages, both these partial conceptions were gradually emended, especially the conception of Aristotle. But the process, as regards Plato, was not completed until the Renaissance...

4. Should religious traditions attempt to combine with, or assimilate themselves to, philosophical traditions? What do religion and philosophy generally have in common, and in what ways are they different?

5. Does the free will defense work, even to the extent of explaining "moral" evil? Is there in fact a logical contradiction between the concept of free will and an omniscient deity? Why or why not?

6. Would we be better off without a belief in free will?

Excerpt:

1

AUGUSTINE OF HIPPO (354–430)

Beware lest any man spoil you through philosophy and vain deceit, after the tradition of men, after the rudiments of the world, and not after Christ.

—Paul, Colossians 2:8

AUGUSTINE, a teenager studying in Carthage in the 370s, begins to ponder what he will one day consider the inevitable shortcomings of human philosophy ungrounded in the word of God. This process begins, as Augustine will later recount in his Confessions, when he reads Cicero’sHortensius, written around 45 b.c.e. The young scholar, unacquainted with either Jewish or Christian Scripture, takes away the (surely unintended) lesson from the pagan Cicero that only faith—a faith that places the supernatural above the natural—can satisfy the longing for wisdom.

“But, O Light of my heart,” Augustine wrote to his god in Confessions (c. 397), “you know that at that time, although Paul’s words were not known to me, the only thing that pleased me in Cicero’s book was his advice not simply to admire one or another of the schools of philosophy, but to love wisdom itself, whatever it might be. . . . These were the words which excited me and set me burning with fire, and the only check to this blaze of enthusiasm was that they made no mention of the name of Christ.”

The only check? To me, this passage from Confessions has always sounded like the many rewritings of personal history intended to conform the past to the author’s current beliefs and status in life—which in Augustine’s case meant being an influential bishop of an ascendant church that would tolerate no dissent grounded in other religious or secular philosophies. By the time he writes Confessions, Augustine seems a trifle embarrassed about having been so impressed, as a young man, by a pagan writer. So he finds a way to absolve himself of the sin of attraction to small-“c” catholic, often secular intellectual interests by limiting Cicero to his assigned role as one step in a fourth-century boy’s journey toward capital-“C” Catholicism. It is the adult Augustine who must reconcile his enthusiasm for Cicero with the absence of the name of Christ; there is no reason why this should have bothered the pagan adolescent Augustine at all. Nevertheless, no passage in the writings of the fathers of the church, or in any personal accounts of the intellectual and emotional process of conversion, explains more lucidly (albeit indirectly) why the triumph of Christianity inevitably begins with that other seeker on the road to Damascus. It is Paul, after all, not Jesus or the authors of the Gospels, who merits a mention in Augustine’s explanation of how his journey toward the one true faith was set in motion by a pagan.

It is impossible to consider Augustine, the second most important convert in the theological firmament of the early Christian era, without giving Paul his due. But let us leave Saul—he was still Saul then—as he awakes from a blow on his head to hear a voice from the heavens calling him to rebirth in Christ. Saul did not have any established new religion to convert to, but Augustine was converting to a faith with financial and political influence, as well as a spiritual message for the inhabitants of a decaying empire. Augustine’s journey from paganism to Christianity was a philosophical and spiritual struggle lasting many years, but it also exemplified the many worldly, secular influences on conversion in his and every subsequent era. These include mixed marriages; political instability that creates the perception and the reality of personal insecurity; and economic conditions that provide a space for new kinds of fortunes and the possibility of financial support for new religious institutions.

Augustine told us all about his struggle, within its social context, in Confessions—which turned out to be a best-seller for the ages. This was a new sort of book, even if it was a highly selective recounting of experience (like all memoirs) rather than a “tell-all” autobiography in the modern sense. Its enduring appeal, after a long break during the Middle Ages, lies not in its literary polish, intellectuality, or prayerfulness—though the memoir is infused with these qualities—but in its preoccupation with the individual’s relationship to and responsibility for sin and evil. As much as Augustine’s explorations constitute an individual journey—and have been received as such by generations of readers—the journey unfolds in an upwardly mobile, religiously divided family that was representative of many other people finding and shaping new ways to make a living; new forms of secular education; and new institutions of worship in a crumbling Roman civilization.

After a lengthy quest venturing into regions as wild as those of any modern religious cults, Augustine told the story of his spiritual odyssey when he was in his forties. His subsequent works, including The City of God, are among the theological pillars of Christianity, butConfessions is the only one of his books read widely by anyone but theologically minded intellectuals (or intellectual theologians). In the fourth and early fifth centuries, Christian intellectuals with both a pagan and a religious education, like the friends and mentors Augustine discusses in the book, provided the first audience for Confessions. That audience would probably not have existed a century earlier, because literacy—a secular prerequisite for a serious education in both paganism and Christianity—had expanded among members of the empire’s bourgeois class by the time Augustine was born. The Christian intellectuals who became Augustine’s first audience may have been more interested than modern readers in the theological framework of the autobiography (though they, too, must have been curious about the distinguished bishop’s sex life). ButConfessions has also been read avidly, since the Renaissance, by successive generations of humanist scholars (religious and secular); Enlightenment skeptics; nineteenth-century Romantics; psychotherapists; and legions of the prurient, whether religious believers or nonbelievers. Everyone, it seems, loves the tale of a great sinner turned into a great saint.

In my view, Augustine was neither a world-class sinner nor a saint, but his drama of sin and repentance remains a real page-turner. Here & Now

==

An old post-

Augustine & string theory

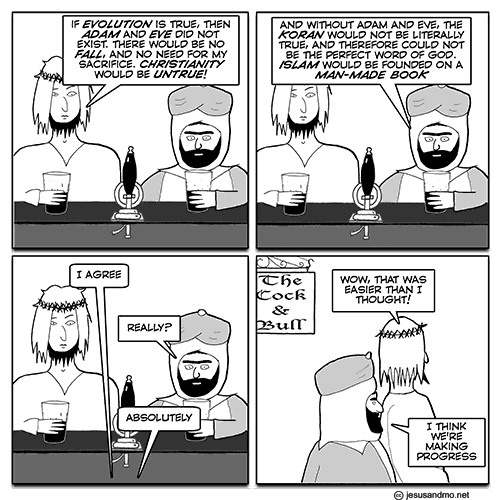

Is anyone, from God on down, “pulling our strings”? We’d not be free if they were, would we? If you say we would, what do you mean by “free”? Jesus and Mo have puzzled this one, behind the wheel with with Moses and with "Free Willy." But as usual, the Atheist Barmaid is unpersuaded.

(As I always must say, when referencing this strip: that’s not Jesus of Nazareth, nor is it the Prophet Mohammed, or the sea-parter Moses; and neither I nor Salman Rushdie, the Dutch cartoonists, the anonymous Author, or anyone else commenting on religion in fictional media are blasphemers. We're all just observers exercising our "god-given" right of free speech, which of course extends no further than the end of a fist and the tip of a nose. We'll be celebrating precisely that, and academic freedom, when we line up to take turns reading the Constitution this morning.

No, they’re just a trio of cartoonish guys who often engage in banter relevant to our purposes in CoPhi. It’s just harmless provocation, and fun. But if it makes us think, it’s useful.)

Augustine proposed a division between the “city of god” and the “earthly city” of humanity, thus excluding many of us from his version of the cosmos. “These two cities of the world, which are doomed to coexist intertwined until the Final Judgment, divide the world’s inhabitants.” SEP

And of course he believed in hell, raising the stakes for heaven and the judicious free will he thought necessary to get there even higher. If there's no such thing as free will, though, how can you do "whatever the hell you want"? But, imagine there's no heaven or hell. What then? Some of us think that's when free will becomes most useful to members of a growing, responsible species.

Someone posted the complaint on our class message board that it's not clear what "evil" means, in the context of our Little History discussion of Augustine. But I think this is clear enough: "there is a great deal of suffering in the world," some of it proximally caused by crazy, immoral/amoral, armed and dangerous humans behaving badly, much more of it caused by earthquakes, disease, and other "natural" causes. All of it, on the theistic hypothesis, is part and parcel of divinely-ordered nature.

Whether or not some suffering is ultimately beneficial, character-building, etc., and from whatever causes, "evil" means the suffering that seems gratuitously destructive of innocent lives. Some of us "can't blink the evil out of sight," in William James's words, and thus can't go in for theistic (or other) schemes of "vicarious salvation." We think it's the responsibility of humans to use their free will (or whatever you prefer to call ameliorative volitional action) to reduce the world's evil and suffering. Take a sad song and make it better.

Note the Manichaean strain in Augustine, and the idea that "evil comes from the body." That's straight out of Plato. The world of Form and the world of perfect heavenly salvation thus seem to converge. If you don't think "body" is inherently evil, if in fact you think material existence is pretty cool (especially considering the alternative), this view is probably not for you. Nor if you can't make sense of Original Sin, that most "difficult" contrivance of the theology shop.

"Augustine had felt the hidden corrosive effect of Adam's Fall, like the worm in the apple, firsthand," reminds Arthur Herman. His prayer for personal virtue "but not yet" sounds funny but was a cry of desperation and fear.

Bertrand Russell, we know, was not a Christian. But he was a bit of a fan of Augustine the philosopher (as distinct from the theologian), on problems like time.

As for Augustine the theologian and Saint-in-training, Russell's pen drips disdain.

That's an allusive segue to today's additional discussion of Aristotelian virtue ethics, in its turn connected with the contradictions inherent in the quest to bend invariably towards Commandments. "Love your neighbor": must that mean, let your neighbor suffer a debilitating terminal illness you could pull the plug on? Or is the "Christian" course, sometimes, to put an end to it?

We also read today of Hume's Law, Moore's Naturalistic Fallacy, the old fact/value debate. Sam Harris is one of the most recent controversialists to weigh in on the issue, arguing that "good" means supportive of human well-being and flourishing, which are in turn based on solid facts. "The answer to the question, 'What should I believe, and why should I believe it?' is generally a scientific one..." Brain Science and Human Values

Also: ethical relativism, meta-ethics, and more. And maybe we'll have time to squeeze in consideration of the perennial good-versus-evil trope. Would there be anything "wrong" with a world in which good was already triumphant, happiness for all already secured, kindness and compassion unrivaled by hatred and cruelty? I think it might be just fine. Worth a try, anyway. Where can I vote for that?

Is anyone, from God on down, “pulling our strings”? We’d not be free if they were, would we? If you say we would, what do you mean by “free”? Jesus and Mo have puzzled this one, behind the wheel with with Moses and with "Free Willy." But as usual, the Atheist Barmaid is unpersuaded.

(As I always must say, when referencing this strip: that’s not Jesus of Nazareth, nor is it the Prophet Mohammed, or the sea-parter Moses; and neither I nor Salman Rushdie, the Dutch cartoonists, the anonymous Author, or anyone else commenting on religion in fictional media are blasphemers. We're all just observers exercising our "god-given" right of free speech, which of course extends no further than the end of a fist and the tip of a nose. We'll be celebrating precisely that, and academic freedom, when we line up to take turns reading the Constitution this morning.

No, they’re just a trio of cartoonish guys who often engage in banter relevant to our purposes in CoPhi. It’s just harmless provocation, and fun. But if it makes us think, it’s useful.)

Augustine proposed a division between the “city of god” and the “earthly city” of humanity, thus excluding many of us from his version of the cosmos. “These two cities of the world, which are doomed to coexist intertwined until the Final Judgment, divide the world’s inhabitants.” SEP

And of course he believed in hell, raising the stakes for heaven and the judicious free will he thought necessary to get there even higher. If there's no such thing as free will, though, how can you do "whatever the hell you want"? But, imagine there's no heaven or hell. What then? Some of us think that's when free will becomes most useful to members of a growing, responsible species.

Someone posted the complaint on our class message board that it's not clear what "evil" means, in the context of our Little History discussion of Augustine. But I think this is clear enough: "there is a great deal of suffering in the world," some of it proximally caused by crazy, immoral/amoral, armed and dangerous humans behaving badly, much more of it caused by earthquakes, disease, and other "natural" causes. All of it, on the theistic hypothesis, is part and parcel of divinely-ordered nature.

Whether or not some suffering is ultimately beneficial, character-building, etc., and from whatever causes, "evil" means the suffering that seems gratuitously destructive of innocent lives. Some of us "can't blink the evil out of sight," in William James's words, and thus can't go in for theistic (or other) schemes of "vicarious salvation." We think it's the responsibility of humans to use their free will (or whatever you prefer to call ameliorative volitional action) to reduce the world's evil and suffering. Take a sad song and make it better.

Note the Manichaean strain in Augustine, and the idea that "evil comes from the body." That's straight out of Plato. The world of Form and the world of perfect heavenly salvation thus seem to converge. If you don't think "body" is inherently evil, if in fact you think material existence is pretty cool (especially considering the alternative), this view is probably not for you. Nor if you can't make sense of Original Sin, that most "difficult" contrivance of the theology shop.

"Augustine had felt the hidden corrosive effect of Adam's Fall, like the worm in the apple, firsthand," reminds Arthur Herman. His prayer for personal virtue "but not yet" sounds funny but was a cry of desperation and fear.

Like Aristotle, Augustine believed that the quality of life we lead depends on the choices we make. The tragedy is that left to our own devices - and contrary to Aristotle - most of those choices will be wrong. There can be no true morality without faith and no faith without the presence of God. The Cave and the Light

Bertrand Russell, we know, was not a Christian. But he was a bit of a fan of Augustine the philosopher (as distinct from the theologian), on problems like time.

As for Augustine the theologian and Saint-in-training, Russell's pen drips disdain.

It is strange that the last men of intellectual eminence before the dark ages were concerned, not with saving civilization or expelling the barbarians or reforming the abuses of the administration, but with preaching the merit of virginity and the damnation of unbaptized infants.Funny, how the preachers of the merit of virginity so often come late - after exhausting their stores of wild oats - to their chaste piety. Not exactly paragons of virtue or character, these Johnnys Come Lately. On the other hand, it's possible to profess a faith you don't understand much too soon. My own early Sunday School advisers pressured and frightened me into "going forward" at age 6, lest I "die before I wake" one night and join the legions of the damned.

That's an allusive segue to today's additional discussion of Aristotelian virtue ethics, in its turn connected with the contradictions inherent in the quest to bend invariably towards Commandments. "Love your neighbor": must that mean, let your neighbor suffer a debilitating terminal illness you could pull the plug on? Or is the "Christian" course, sometimes, to put an end to it?

We also read today of Hume's Law, Moore's Naturalistic Fallacy, the old fact/value debate. Sam Harris is one of the most recent controversialists to weigh in on the issue, arguing that "good" means supportive of human well-being and flourishing, which are in turn based on solid facts. "The answer to the question, 'What should I believe, and why should I believe it?' is generally a scientific one..." Brain Science and Human Values

Also: ethical relativism, meta-ethics, and more. And maybe we'll have time to squeeze in consideration of the perennial good-versus-evil trope. Would there be anything "wrong" with a world in which good was already triumphant, happiness for all already secured, kindness and compassion unrivaled by hatred and cruelty? I think it might be just fine. Worth a try, anyway. Where can I vote for that?

"Boethius in his cell imagined his visitor: Philosophy personified as a tall woman wearing a dress with the letters Pi to Theta on it. She berates him for deserting her and the stoicism she preached. Boethius’s own book was a response to her challenge..." (from Nigel's essay "Philosophy Should Be Conversation")

==

COLLEGE students tell me they know how to look someone in the eye and type on their phones at the same time, their split attention undetected. They say it’s a skill they mastered in middle school when they wanted to text in class without getting caught. Now they use it when they want to be both with their friends and, as some put it, “elsewhere.” These days, we feel less of a need to hide the fact that we are dividing our attention. In a 2015 study by the Pew Research Center, 89 percent of cellphone owners said they had used their phones during the last social gathering they attended. But they weren’t happy about it; 82 percent of adults felt that the way they used their phones in social settings hurt the conversation.I’ve been studying the psychology of online connectivity for more than 30 years. For the past five, I’ve had a special focus: What has happened to face-to-face conversation in a world where so many people say they would rather text than talk? I’ve looked at families, friendships and romance. I’ve studied schools, universities and workplaces. When college students explain to me how dividing their attention plays out in the dining hall, some refer to a “rule of three.” In a conversation among five or six people at dinner, you have to check that three people are paying attention — heads up — before you give yourself permission to look down at your phone. So conversation proceeds, but with different people having their heads up at different times. The effect is what you would expect: Conversation is kept relatively light, on topics where people feel they can drop in and out... (from Sherry Terkle's "Stop Googling. Let's Talk")

==

Sherry Turkle is a singular voice in the discourse about technology. She’s a skeptic who was once a believer, a clinical psychologist among the industry shills and the literary hand-wringers, an empiricist among the cherry-picking anecdotalists, a moderate among the extremists, a realist among the fantasists, a humanist but not a Luddite: a grown-up. She holds an endowed chair at M.I.T. and is on close collegial terms with the roboticists and affective-computing engineers who work there. Unlike Jaron Lanier, who bears the stodgy weight of being a Microsoft guy, or Evgeny Morozov, whose perspective is Belarussian, Turkle is a trusted and respected insider. As such, she serves as a kind of conscience for the tech world.

Turkle’s previous book, “Alone Together,” was a damning report on human relationships in the digital age. By observing people’s interactions with robots, and by interviewing them about their computers and phones, she charted the ways in which new technologies render older values obsolete. When we replace human caregivers with robots, or talking with texting, we begin by arguing that the replacements are “better than nothing” but end up considering them “better than anything” — cleaner, less risky, less demanding. Paralleling this shift is a growing preference for the virtual over the real. Robots don’t care about people, but Turkle’s subjects were shockingly quick to settle for the feeling of being cared for and, similarly, to prefer the sense of community that social media deliver, because it comes without the hazards and commitments of a real-world community. In her interviews, again and again, Turkle observed a deep disappointment with human beings, who are flawed and forgetful, needy and unpredictable, in ways that machines are wired not to be. Her new book, “Reclaiming Conversation,” extends her critique, with less emphasis on robots and more on the dissatisfaction with technology reported by her recent interview subjects. She takes their dissatisfaction as a hopeful sign, and her book is straightforwardly a call to arms: Our rapturous submission to digital technology has led to an atrophying of human capacities like empathy and self-reflection, and the time has come to reassert ourselves, behave like adults and put technology in its place... (Jonathan Franzen review of Reclaiming Conversation, continues)

==

A follow-up from Sherry Turkle on the lost art of conversation:

My recent Sunday Review essay, adapted from my book “Reclaiming Conversation,” made a case for face-to-face talk. The piece argued that direct engagement is crucial for the development of empathy, the ability to put ourselves in the place of others. The article went on to say that it is time to make room for this most basic interaction by first accepting our vulnerability to the constant hum of online connection and then designing our lives and our products to protect against it.

Some readers agreed with me. Others, even as they disagreed, captured the fragility of conversation today... (continues)

Though one goal of visiting a professor during office hours is certainly transactional — to increase your knowledge and improve your grade — the other is to visit someone who is making an effort to understand you and how you think. And a visit to a professor holds the possibility of giving a student the feeling of adult support and commitment.

But students say they don’t come to office hours because they are afraid of being too dull. They tell me they prefer to email professors because only with the time delay and the possibility of editing can they best explain their work. My students suggest that an email from them will put me in the best position to improve their ideas. They cast our meeting in purely transactional terms, judging that the online transaction will yield better results than a face-to-face meeting.

Zvi, a college junior who doesn’t like to see his professors in person but prefers to email, used transactional language to describe what he might get out of office hours: He has ideas; the professors have information that will improve them. In the end, Zvi walked back his position and admitted that he stays away from professors because he doesn’t feel grown-up enough to talk to them. His professors might be able to help him with this, but not because they’ll give him information.

Studies of mentoring show that what makes a difference, what can change the life of a student, is the presence of a strong figure who shows an interest, who, as a student might say, “gets me.”

You need face-to-face conversation for that. nyt

==

*From Consolation of Philosophy, Book V-'Since, then, as we lately proved, everything that is known is cognized not in accordance with its own nature, but in accordance with the nature of the faculty that comprehends it, let us now contemplate, as far as lawful, the character of the Divine essence, that we may be able to understand also the nature of its knowledge...

I came to a conclusion on free will and the possibility of an omniscient deity well before now... illusion. Even if you consider how we make decisions without clouding the concept with any sort of religious context it still boils down to illusion. All of our decisions are made in our brains; our brains process stimuli from the outside world and from within as our biology allows, and choices are made. We make different decisions because our brains are wired differently, from both genetics and experience. To say that we have “free will” is to say we can step outside of ourselves, or these mental processes, and make decisions. It seems we must be free of ourselves to have free will. I hope I made my point clear enough. What do you think? #11

ReplyDeleteI think you make some really credible and insightful points. It's easy to convince oneself that free will exists and we have the power to decide for ourselves, because it really does feel that way sometimes. But once the fundamental biological processes are understood and put into the mix, it's difficult to deny its control. I mean, I do know that our brain has made its decision a few moments before we are consciously aware of it, which compliments your point. It's definitely complicated, yet fascinating stuff.

DeleteSection #6

LH 6-8

ReplyDelete1. How did Augustine "solve" the problem of evil in his younger days, and then after his conversion to Christianity? Why wasn't it such a problem for him originally?

2. What does Boethius not mention about himself in The Consolation of Philosophy?

3. Boethius' "recollection of ideas" can be traced back to what philosopher?

4. What uniquely self-validating idea did Anselm say we have?

5. Gaunilo criticized Anselm's reasoning using what example?

6. What was Aquinas' 2nd Way?

1.He was a Manichaean, which mean he didn’t believe that God was supremely powerful. To him, God and Satan were locked in an ongoing battle for control, and no one was stronger than the other; after his conversion to Christianity, he realized the power of evil still remained. His solution was the existence of free will.

2.Philosophy’s answer to where Boethius can find true happiness wasn’t included in The Consolation of Philosophy.

3.Plato

4.An idea of God

5.A perfect island

6.The First Cause Argument, which provides proof for God’s existence.

Thank you for posting this! Theres always one or two that I can never find

DeleteFL 21

ReplyDelete9. By the end of the '50s how much TV did the average American watch?

10. Who was the Steve Jobs of his era?

11. Of what was Disneyland "more or less a replica"?

12. What fantasy did Hugh Hefner promote?

13. Who was our "ad hoc national Pastor-in-Chief"?

14. In the second year of Eisenhower's presidency (1954), what was inserted into the Pledge of Allegiance?

9. Americans spent about a third of their waking hours watching tv.

10. Walt Disney

11. Main Street USA

12. He built out a 360-degree fantasy that seemed normal, an aspirational template for his wankers to reimagine their everyday lives fantastically.

13. Billy Graham

14. “under God”

14. In the second year of Eisenhower's presidency (1954), what was inserted into the Pledge of Allegiance?

DeleteIn God we trust

Is it better to embrace (or renounce) religious faith early in life, or to "sow your wild oats" and enjoy a wide experience of the world before committing to any particular tradition or belief? Were you encouraged by adults, in childhood, to make a public profession of faith? If so, did you understand what that meant or entailed?

ReplyDeleteIn my opinion, it would definitely be wise to allow yourself to gain an extensive knowledge of the world and religion before claiming anything. This allows yourself to think with different perspectives about the world. I was encouraged by a significant portion of my family to claim Christianity. I have close family members that are pastors and I started off in the church, so at some point there was pressure to be Christian. I was definitely encouraged to make a public profession of faith because before I decided not to be Christian, I took part in a lot of Christian practices. I was baptized, I was in a purity ceremony, I celebrated Christmas and Easter, etc. At the time, I didn’t understand why I was required to do these things, but as I grew older and started studying and asking more questions, I realized why.

I agree, I think people celebrate holidays and not know the real reason behind the holiday itself.

DeleteI agree. Young people (or anyone for that matter) should be more encouraged to explore their options and decide for themselves rather than following into the exact lives that their family has lived. I feel like people would be genuinely happier in their lives if they knew that they didn't have to follow a certain way.

Deletesection #5

By the end of the '50s how much TV did the average American watch? An average American watched approximately 5 hours per day

ReplyDeleteIs it better to embrace (or renounce) religious faith early in life, or to "sow your wild oats" and enjoy a wide experience of the world before committing to any particular tradition or belief? Were you encouraged by adults, in childhood, to make a public profession of faith? If so, did you understand what that meant or entailed?

ReplyDeleteI believe that it is better to think things through before making any decisions. I was encouraged to become a christian by many people but in the end it was my decision and I still believe that I made the right choice. Its never good to force a belief on someone but there is always a way that you can better explain your beliefs.

I think making your own decisions is important as well, and people learn not to do things after they have already done them. But I think you can embrace faith early, but still learn more about yourself and you will always make mistakes, best not to beat your self over as much and learn what can you do better next time.

DeleteMichael DeLay #5

You can definitely do both. A lot of children embrace religion early in life because it is what they are told to do by their parents, and children are supposed to always listen and trust their parents. But then the children get older and they may see the world in a different light. Or maybe they won't.

DeletePersonally, I believe we should think things through and experience things for ourselves before making decisions. But no harm no foul, because we all have the freedom to change our practices at any time in life.

Does the concept of a never-ending struggle between good and evil appeal to you?

ReplyDeleteYes, I believe in the forces of Satan and God and there is a constant battle between the two that will end at the second coming of Christ.

I agree, because I am a Christian so I believe this is true but That God has already won but there still will continue to be evil in this world.

DeleteMichael DeLay #5

I also agree. I was never a huge churchgoer but definitely believe in the faith and am Christian, and I also believe that there will always be a imminent struggle. It is the whole point of the battle constantly going between Christ and Devil, trying to "persuade" you one way or the other.

DeleteSection #6

I believe that the battle between Satan and God explains why people struggle to do the right thing. If this struggle never existed, these bad actions would be attributed to God, even though we know that this isn't true.

Deletesection 6

"Which is more plausible, that God exists but is not more powerful than Satan, or that neither God nor Satan exists? Why?"

ReplyDeleteI have gone to church with my cousins growing up and I have tried to believe, but I find it hard to do. Mainly because the Bible has been modified numerous times so it's hard to trust that everything in the book. I don't think I could ever believe that God and Satan exist due to the fact that I have never had an experience with either.

I see your point, however there are people who believe in one or not the other and maybe even both and haven't had experience with either too.

DeleteI'm not trying to persuade you or anything like that but just know that you are here for a reason. And that reason could be anything but in religious view point, the reason is God. And if God (Good) exist there is always Satan(Evil).

Delete"Are supernatural stories of faith, redemption, and salvation more comforting to you than the power of reason and evidence?"

ReplyDeleteI've grown to be a skeptical person; I'm constantly questioning things. If someone told me something happened because God wanted it to I'm going to ask why to every reason they give me. I'm not disrespectful in anyway towards anyone who believes in something that I'm struggling to believe in myself. I find reason and evidence more comforting in my opinion because I can actually see it, test it, question it, and all of those good things. Facts, good or bad, are what put my mind at ease.

I agree with you! At times however there are things I seem to be comforted better when I have faith. It all has to do with the type of situation for me.

DeleteI agree with you it is still taking me to this day to really believe in faith fully I still question.

DeleteSection 11

"If you were falsely imprisoned, tortured, and scheduled for execution, would you be able to achieve "consolation"? How?"

ReplyDeleteI don't think I would ever be able to find consolation if I had to endure those types of events. It took me a few weeks alone to be comfortable driving again after someone ran a red light and almost clipped my front end years ago. I could not imagine how mentally unstable I would become if I had to go to prison and scheduled for execution or tortured. It could be possible with the help of family and a new environment would allow me to seek consolation, but even that would be pushing it 😆.

Yes I agree! I feel like since you've seen a side that not many people see of society, consolation would be hard.

DeleteIf you were falsely imprisoned, tortured, and scheduled for execution, would you be able to achieve "consolation"? How?

ReplyDeleteI do not think I would ever be able to achieve consolation because I would know that I was not guilty. I do not think that anyone would be able to over come this because they would know that they did not deserve how they were being treated or being imprisoned.

I agree if I was not wrong in the doing then I would not be able to bring myself to the point of consolation. Section 11

DeleteI agree, I don't think anyone likes to be falsely accused of anything they didn't do. And to bring yourself to a point of consolation would be extremely hard, unless you've made peace and contentment with your life

DeleteMichael DeLay #5

Oh yeah, I'm definitely with y'all that achieving true consolation would be close to impossible. I can't imagine how much inner turmoil and anger I would feel if I ever had to deal with such an injustice. I do think it's possible, however, to reach consolation. Of course, it would take a great deal of soul searching and genuine acceptance and forgiveness, which many of us rightfully wouldn't be able to give.

DeleteSection #6

Is it better to embrace (or renounce) religious faith early in life, or to "sow your wild oats" and enjoy a wide experience of the world before committing to any particular tradition or belief? Were you encouraged by adults, in childhood, to make a public profession of faith? If so, did you understand what that meant or entailed?

ReplyDeleteI think that everyone is different. Personally I was not influenced by anyone about what faith I should follow. I think that is a good thing because I think when it comes to religious faith, we should be able to explore our options freely without the persuasion of others. From experience, when I am forced to do something I tend to hate the task.

I agree with your statement because at the end of the day you what is best and works best for you.

DeleteSection 11

I agree. Anytime anyone feels forced to do something they are more reluctant and will want to do the opposite. The only thing to do in this instance is to gather as much information as possible and make your own decision.

DeleteWhich is more plausible, that God exists but is not more powerful than Satan, or that neither God nor Satan exists? Why?

ReplyDeleteI'd have to say that neither would exist in the scenario that Satan is more powerful than God. In that instance, Satan IS God. Kinda a scary thought. To be God means to be all powerful, which by definition is not compatible with the first scenario.

I really like your take on this. I honestly didn't really think about it from that angle. I think there are many people who would find the idea of Satan being God as plausible, due to the theory that we're actually in hell right now. Regardless, I agree with everything you said.

DeleteSection #6

How does the definition of God as omniscient, omnipotent, and perfectly good make it harder to account for evil and suffering in the world? Would it be better to believe in a lesser god, or no god at all?

ReplyDeleteI think you are perfectly able to believe in suffering, while believing in God. As a Coptic Orthodox Christian, I believe God grants us with free will. I also believe that God allows suffering, which allows us to lean on Him, as opposed to being self reliant and having no faith in Him.

I agree. I believe that God gave us the freedom of choice and it is our choice that decides what kind of lives we lead through our suffering.

DeleteI think that's a really good way to put it. If we constantly had good all the time with no bad or suffering, I find it hard to believe that we would know how yo appreciate the good. I believe that God knows what he is doing, and I think we know how to understand it.

DeleteJoseph Cooper #11

ReplyDeleteCan the definition of a word prove anything about the world?

Definitions can prove that there a common ground to stand on. It puts what is being discussed into a clear view so what it can looked upon objectively.

Does the possibility of other worlds somehow diminish humanity?

No, it actually gives us more to strive for. Other worlds with other cultures give us the opportunity to expand ourselves. The only thing that diminishes us is if we do not cease the opportunity.

Does the concept of a never-ending struggle between good and evil appeal to you? Does it make sense, in the light of whatever else you believe? Would there be anything "wrong" with a world in which good was already triumphant, happiness for all already secured, kindness and compassion unrivaled by hatred and cruelty?

The concept that the wicked will be punished by the righteous in a constant battle for what is right is something more in line with fiction than reality. Reality is actions are taken for benefit the yield and then judged on their inherent "good" or "evil" after the fact. A world where good is triumphant is one that reflection is bypassed and actions are not further examined. There is no world where everything is good for everyone, only one where we ignore reality

I think that your analysis of other worlds diminishing our humanity is spot on. The possibility of more than one world should make us more eager. Not diminish us.

DeleteDoes the concept of a never-ending struggle between good and evil appeal to you?

ReplyDeleteYes the concept of the never ending battle does appeal to me because we are brought to believe that good will always defeat evil and yet we still deal with the good and bad to this day. Section 11

I agreed. There so many good things that can happen to us but evil has to be our first step in order to get the goods.

DeleteI feel like as long as there is good in the world there will always be bad. There will always be criminals and always be "evil." There will always be good and the people who dedicate there lives to help others.

Delete^^^ Michael DeLay #5

DeleteI agree. Where there is light there will always be shadows. Where there is good there will always be evil.

DeleteI agree. There will has be some form of bad to go against the good to test the limits. Section 11

DeleteWhich is more plausible, that God exists but is not more powerful than Satan, or that neither God nor Satan exists? Why?

ReplyDeleteI believe that God does exists and as stated in the bible, Satan was actually trying to take over God but he couldn't.

If you were falsely imprisoned, tortured, and scheduled for execution, would you be able to achieve "consolation"? How?

ReplyDeleteI'm not sure how I would feel. I would probably feel cheated. For being falsely accused of something. I would probably be angry and ask why is this happening. It would be like they were murdering me instead of bringing someone to justice.

Michael DeLay #5

I agree. It seems like it would be deep, wretching feeling that you could never get to go away.

DeleteSection #6

Which is more plausible, that God exists but is not more powerful than Satan, or that neither God nor Satan exists? Why?

ReplyDeleteI believe that God is an omnipotent being and Satan is less powerful than him but still tried to take control (and failed).

Not an answer to a question but just giving my two cents on free will. I believe in free will considering I can either write this or not and post it or not and I am entirely in control of my finger to click "Publish." However, it can be found through logical reasoning that everyone must will for their own perceived good. Meaning that no matter what we choose to do we always choose what we see as the good. So to an extent we do not have free will because we must choose the good, but why would anyone want to choose something they see as not good for themselves anyways.

ReplyDeleteAbsolutely, and since there are those who do wrong by others, they chose to act that way. After all a sin cannot be committed without the free will to act against Him.

DeleteSection 11

Can you explain the concept of Original Sin? Do you think you understand it?

ReplyDeleteI think that I understand it. I know the concept is that sin is bred into all human and descended from the fall of adam and eve in the garden. So therefore all human descendants below them (us) have an "excuse" or it is our "nature" to sin. At the same time I believe I understand it I'm sure there is way more to it than I realize.

Section #6

I would interpret original sin in the same sense. It is the belief that we are all born with the tendency to "sin" but I also am more lenient on what I believe is actually a sin versus what men have created to be evil (such as alcohol and sex).

Delete(Section #5, comment 4) I think this is my 31st base ***

Is it better to embrace (or renounce) religious faith early in life, or to "sow your wild oats" and enjoy a wide experience of the world before committing to any particular tradition or belief? Were you encouraged by adults, in childhood, to make a public profession of faith? If so, did you understand what that meant or entailed? In my experience, I was born into a religion and ran with that religion. I do see, however, how experiencing world events later down the road could better help you understand your view on religion.

ReplyDeleteIf you were falsely imprisoned, tortured, and scheduled for execution, would you be able to achieve "consolation"? How? I would like to think that I would be able to achieve consolation but I guess I wouldn’t really know until I was put into that position. It would be hard to not question your faith being falsely accused and even executed.

Is theoretical simplicity always better, even if the universe is complex? I think in most cases simplicity could benefit everyone. Unfortunately, the world we live in really doesn’t allow for simplicity. We want the biggest and best things rather than sitting back and looking at it from a simplistic view.

"Which is more plausible, that God exists but is not more powerful than Satan, or that neither God nor Satan exists? Why?"

ReplyDeleteIt is more plausible to believe that there are good people and bad people and those people should not spend eternity in the same place/ state. I believe not in a man that is God and a man that is Satan but a spiritual realm that people's souls go to rest at after they pass. I do not think that there are physical people in heaven and hell, but I do believe that good is greater than evil and that this undeniably exists.

Very true. After all the only power satan needs to be more powerful than God is persuasion. But to think that a world could exist without God is obscured.

DeleteSection 11

ReplyDelete"Are supernatural stories of faith, redemption, and salvation more comforting to you than the power of reason and evidence?"

The power of reason and evidence are what ultimately gives me peace when thinking about things in everyday life. But, when I think about what will become of me when I die, I have to rely on some belief that there is at least some state of eternal peace that I will be in when the time comes. It brings me comfort to know that this is not all for nothing and I will not be miserable or non-existent in death. (Section #5, comment 2)

ReplyDeleteWhat do you think of the Manichean idea that an "evil God created the earth and emtombed our souls in the prisons of our bodies"? 392

I think that Manichean must have lived a miserable life because I do not feel like I am a prisoner within my body. I enjoy my life and feel thankful to have been given it. (Section #5, comment 3)

Many Christians and Platonists (among others) do often speak of the body as prison for the spirit or soul. Socrates himself (as Plato has him speak) greeted the death of his body as a release from internment and a cure from the disease of life ("I owe a cock to Aesclepius," the god of healing arts). I've never quite understood why Socrates would have said such a thing, having so obviuosly relished and enjoyed his life. But it's not uncommon for there to be a disconnect between the way an individual lives and the things he's been taught to believe (or made to say in a dialogue written by someone else).

DeleteTo all who've said they believe (with Augustine) that free will accounts for suffering: how does free will relate to natural catastrophes like earthquakes, floods, tornadoes... ?

ReplyDeleteAnd even if you think free will is somehow responsible for deadly viral infections like COVID-19, how do you reconcile the fact that the victims of scourge typically are NOT those whose bad choices had anything to do with the spread of the disease? In particular, to echo Dostoevesky's question in The Brothers Karamazov, how do you make sense of the suffering and dying of innocent children?

"Are supernatural stories of faith, redemption, and salvation more comforting to you than the power of reason and evidence? "

ReplyDeleteI find more comfort in the power of reason and evidence because its just something that logically makes more sense to me. I can see the evidence and how it ties into certain things without having to go out on a limb and hope that something exists. i feel like it would be easier to go with the religious take and just believe things without concrete evidence because then you are free to imagine a world or place that is better than were you are now than except the harsh reality that you are facing. this gives people hope but i believe it to be false hope. well whatever gets you through the day right? to each his own. (section #6)

"What do you think of the Manichean idea that an "evil God created the earth and entombed our souls in the prisons of our bodies"?"

ReplyDeletei personally think that this idea has as much credit as any other religious idea. if one is possible all are possible. if this were the truth and we are just prisoners here on earth to be possibly watched over by an evil god as some sort of entertainment i would still live the life that im living. maybe knowing that this evil god did this as some sort of punishment would create a hatred toward him and we would have someone to actually blame for things that go wrong in our lives, sort of like how people treat satan. (section #6)

"Is it better to embrace (or renounce) religious faith early in life, or to "sow your wild oats" and enjoy a wide experience of the world before committing to any particular tradition or belief? Were you encouraged by adults, in childhood, to make a public profession of faith? If so, did you understand what that meant or entailed?"

ReplyDeletei think it is better to have a wide range of experiences before making a choice to commit or denounce religious faith. doing either of those without having experienced it all would be a bad decision. if you commit early on to religion without outside experiences i feel like you are being brain washed into believing it especially if you are a young child who doesn't know better. having experienced life and hardships and then still choosing to believe in religion after all that then you really know what your beliefs are, or vice versa. (section #6)

"If you were falsely imprisoned, tortured, and scheduled for execution, would you be able to achieve "consolation"? How?"

ReplyDeletei dont think it would be possible for me to reach any type of consolation that depends on an outside view of things or a feeling of fairness but i would reach a conviction from my own self in the sense that i know that i did not do anything wrong and lived my life the way i wanted to up until the end. being at peace with one self without letting outside things influence you is something that i think everyone should strive for and would make the world a better place. (section #6)

Beautifully said Miguel. I agree, being at peace with one self would be the best possible state of mind you can create for yourself.

DeleteSection 11

Can you explain the concept of Original Sin? Do you think you understand it?

ReplyDelete-- When committing sin there are really two sins being committed. The sin itself and the original sin which is the disobedience to God to commit the sin.

Section 11

DeleteCan you explain the concept of Original Sin? Do you think you understand it?

DeleteThe original sin is disobedience trying to be like God. Lucifer the snake was the most powerful angel in heaven he was over the music and praise and he got selfish and wanted that glory for himself , which is way he fell and he wants more people to follow him. So satan knew what he was doing when he tricked Eve and Adam by tempting their flesh and asked them " Dont you want to be like God?" and whenever we sin we try to be like God by fulfillling our fleshly desires ourselves.

Does the possibility of other worlds somehow diminish humanity?

ReplyDeleteIt depends on one's perspective. I can definitely see why people would feel lesser than with the knowledge that there are other worlds, because then that would mean we aren't the center of attention or the one-of-a-kind creation that many religions emphasize. This makes people feel less special and might make them believe that humanity isn't as important as they previously thought. However, the possibility of other worlds has the ability to force people into paying attention to things greater than themselves and can wake people up to the idea of the greater good. This could then cause one to view humanity as even more important than before.

Section #6

Do you find the concept of Original Sin compelling, difficult, unfair, or dubious? In general, do we "inherit the sins of our fathers (and mothers)"? If yes, give examples and explain.

ReplyDeleteI could see why one might classify it as unfair, but I don't see it that way because it means we're all born into the same playing field. If coming from your particular parents inherently made you more sinful than someone from more "righteous" parents, then yes, I would find it unfair. I don't necessarily find it dubious because, it's true, sin is inevitable. That is, making mistakes and falling short from perfect is a part of life and growing as a human.

In my opinion, I think we do inherit the sins of our parents and those before us. I'm not necessarily talking about in a Biblical sense, but more in a biological and earthly one. We inherit the bad genes and the likelihood of certain behaviors from our mothers and fathers. We inherit the condition of our world and have to account for the poor choices the generations before us made.

Section #6

"If you were falsely imprisoned, tortured, and scheduled for execution, would you be able to achieve "consolation"? How?"

ReplyDeleteI do not think i could reach any form on consolation. To me I would have to fight for my freedom as strong as i could to get back to my family.

I completely agree with you Dylan I couldn't go on knowing that I was wrongly accused.

DeleteSection 11

Does the possibility of other worlds somehow diminish humanity?

ReplyDeleteTo me the possibility of other worlds that are inhabited has no impact on our own humanity, however it would reduce the uniqueness of our own sentience. To me this would be a net positive because there humanity's arrogance is due in large part to our superiority.

I agree with you, when one thinks about the possibility of life outside of earth it challenges these notions of superiority and selfishness that we as people tend to hold without even realizing it. Actually having life on other planets could in fact stand to humble us a little, and maybe help us develop more humanity for ourselves, our planet, and for the potential of more.

DeleteDo you find the concept of Original Sin compelling, difficult, unfair, or dubious? In general, do we "inherit the sins of our fathers (and mothers)"? If yes, give examples and explain.

ReplyDeleteI disagree with this concept because this would diminish the concept of a fair God. People are responsible for their own actions and no one else's.

That is true we can't put it on others when it is us who chooses what we do.

DeleteSection 11

Can the definition of a word prove anything about the world?

ReplyDeleteI believe in some ways a word can define the word but it would only be accurate by a hair because the world is always changing and evolving to where not one word can really define it. But, the people have a huge affect as into why because we all have different perspective on the world.

Section 11

March 24

ReplyDeleteI posted on the "can the definition of a ward prove anything about the world?

I replied to Dylan's Do you find the concept of originals in compelling...and if you were falsely imprisoned, tortured...

I also replied to Anonymous Section 11's Does the concept of a never-ending struggle between good and evil appeal to you ?

I also did the quiz questions

DeJah Section 11

I do honestly believe that it is good for people to go out and explore themselves in the context of religion or "sow our wild oats". As a child, I went to a religious school and daycare. Often they would preach at us about sin and following God's word. Each summer I would feel so afraid of what it would mean to not be religious that I would get saved. Every summer. Obviously because I was a child I had no real understanding of what I was doing, and for the most part I had no real understanding of any other religion. This brought forth a lot of resentment toward religion as I got older and realized the harm it caused me as a child. Had I been exposed to more facts about Christianity and exposed to other religious faiths perhaps I would have come to a different understanding as an adult.

ReplyDelete#11

In my opinion, the concepts of good and evil are much to black and white to have any true holding in reality. Nothing is pure evil just has nothing is pure good, and having all of either would negatively impact our lives. Everything we do, all of the things we have experienced in life have been a mixture of good times and bad. it has shaped the person you are today and has taught you lessons in life that you otherwise would have never learned. Sure, it would be nice if everything was perfect all the time, but without having those dark time we would never learn to appreciate the good things we do have in our life.

ReplyDelete#11

How does the definition of God as omniscient, omnipotent, and perfectly good make it harder to account for evil and suffering in the world? Would it be better to believe in a lesser god, or no god at all?

ReplyDeleteThe definition obviously has problems because it then begs us to ask, "Well, if God is so great, why did he allow this plague to kill so many innocent people?" and it's a very difficult questions for believer's to convincingly answer. I've always believed that if God really did put the universe into motion, then he's clearly kept his hands out of our little lives since. Therefore, if God does exist, there's no way he's intervening to avert the crises our world faces daily.