A collaborative search for wisdom, at Middle Tennessee State University and beyond... "The pluralistic form takes for me a stronger hold on reality than any other philosophy I know of, being essentially a social philosophy, a philosophy of 'co'"-William James

Saturday, December 29, 2018

Thursday, December 27, 2018

To Deal With Trump, Look to Voltaire

Advice from the Enlightenment: In the face of crude bullying and humorless lies, try wit and a passion for justice.

We are living through a climate change in politics. Bigotry, bullying, mendacity, vulgarity — everything emitted by the tweets of President Trump and amplified by his followers has damaged the atmosphere of public life. The protective layer of civility, which makes political discourse possible, is disappearing like the ozone around Earth.

How can we restore a healthy climate? There is no easy answer, but some historic figures offer edifying examples. The one I propose may seem unlikely, but he transformed the climate of opinion in his era: Voltaire, the French philosopher who mobilized the power of Enlightenment principles in 18th-century Europe.

O.K., I know that only an academic like myself would come up with such a proposition. Who in the United States has any interest in Voltaire? College students sometimes read his “Candide” as a novella, and audiences have enjoyed it as an operetta by Leonard Bernstein. But the book ends with a refrain that sounds like quietism: “Let us cultivate our garden.”

Actually, I think that last line, which is among the most famous in all literature, should be understood as a call to engagement. “Cultivation” means commitment to culture, to civility, to civilization itself. That is the argument I want to make... (continues)

By Robert Darnton, nyt

How can we restore a healthy climate? There is no easy answer, but some historic figures offer edifying examples. The one I propose may seem unlikely, but he transformed the climate of opinion in his era: Voltaire, the French philosopher who mobilized the power of Enlightenment principles in 18th-century Europe.

O.K., I know that only an academic like myself would come up with such a proposition. Who in the United States has any interest in Voltaire? College students sometimes read his “Candide” as a novella, and audiences have enjoyed it as an operetta by Leonard Bernstein. But the book ends with a refrain that sounds like quietism: “Let us cultivate our garden.”

Actually, I think that last line, which is among the most famous in all literature, should be understood as a call to engagement. “Cultivation” means commitment to culture, to civility, to civilization itself. That is the argument I want to make... (continues)

By Robert Darnton, nyt

Tuesday, December 25, 2018

Monday, December 24, 2018

Thursday, December 20, 2018

Cicero's dream

- In 1968, Apollo 8 realised the 2,000-year-old dream of a Roman philosopher ... https://buff.ly/2PUC6UN

Half a century of Christmases ago, the NASA space mission Apollo 8 became the first manned craft to leave low Earth orbit, atop the unprecedentedly powerful Saturn V rocket, and head out to circumnavigate another celestial body, making 11 orbits of the moon before its return. The mission is often cast in a supporting role – a sort of warm up for the first moon landing. Yet for me, the voyage of Borman, Lovell and Anders six months before Neil Armstrong’s “small step for a man” will always be the great leap for humankind.

Apollo 8 is the space mission for the humanities, if ever there was one: this was the moment that humanity realised a dream conceived in our cultural imagination over two millennia ago. And like that first imagined journey into space, Apollo 8 also changed our moral perspective on the world forever.

In the first century BC, Roman statesman and philosopher Marcus Tullius Cicero penned a fictional dream attributed to the Roman general Scipio Aemilianus. The soldier is taken up into the sphere of distant stars to gaze back towards the Earth from the furthest reaches of the cosmos:

And as I surveyed them from this point, all the other heavenly bodies appeared to be glorious and wonderful — now the stars were such as we have never seen from this earth; and such was the magnitude of them all as we have never dreamed; and the least of them all was that planet, which farthest from the heavenly sphere and nearest to our earth, was shining with borrowed light, but the spheres of the stars easily surpassed the earth in magnitude — already the earth itself appeared to me so small, that it grieved me to think of our empire, with which we cover but a point, as it were, of its surface.

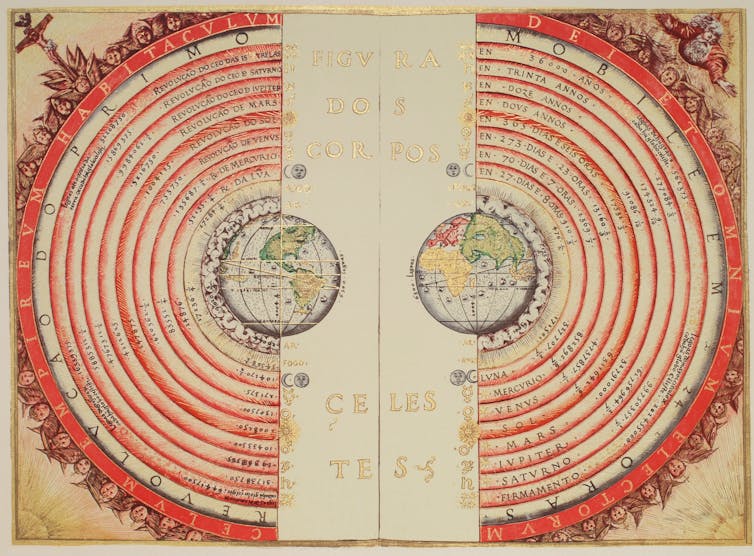

Earth-centric

Even for those of us who are familiar with the ancient and medieval Earth-centred cosmology, with its concentric celestial spheres of sun, moon, planets and finally the stars wheeling around us in splendid eternal rotation, this comes as a shock. For the diagrams that illustrate pre-modern accounts of cosmology invariably show the Earth occupying a fair fraction of the entire universe.

Cicero’s text informs us right away that these illustrations are merely schematic, bearing as much relation to the actual imagined scale of the universe as today’s London Tube map does to the real geography of its tunnels. And his Dream of Scipio was by no means an arcane musing lost to history – becoming a major part of the canon for succeeding centuries. The fourth century Roman provincial scholar Macrobius built one of the great and compendious “commentaries” of late antiquity around it, ensuring its place in learning throughout the first millennium AD.

Cicero, and Macrobius after him, make two intrinsically-linked deductions. Today we would say that the first belongs to science, the second to the humanities, but, for ancient writers, knowledge was not so artificially fragmented. In Cicero’s text, Scipio first observes that the Earth recedes from this distance to a small sphere hardly distinguishable from a point. Second, he reflects that what we please to call great power is, on the scale of the cosmos, insignificant. Scipio’s companion remarks:

I see, that you are even now regarding the abode and habitation of mankind. And if this appears to you as insignificant as it really is, you will always look up to these celestial things and you won’t worry about those of men. For what renown among men, or what glory worth the seeking, can you acquire?

The vision of the Earth, hanging small and lowly in the vastness of space, generated an inversion of values for Cicero; a human humility. This also occurred in the case of the three astronauts of Apollo 8.

A change in perspective

There is a vast difference between lunar and Earth orbit – the destination of all earlier space missions. “Space” is not far away. The international space station orbits, as most manned missions, a mere 250 miles above our heads. We could drive that distance in half a day. The Earth fills half the sky from there, as it does for us on the ground.

But the moon is 250,000 miles distant. And so Apollo 8, in one firing of the S4B third stage engine to leave Earth orbit, increased the distance from Earth attained by a human being by not one order of magnitude, but three. From the moon, the Earth is a small glistening coin of blue, white and brown in the distant black sky.

So it was that, as their spacecraft emerged from the far side of its satellite, and they saw the Earth slowly rise over the bleak and barren horizon, the crew grabbed all cameras to hand and shot the now iconic “Earthrise” pictures that are arguably the great cultural legacy of the Apollo program. Intoning the first verses from the Book of Genesis as their Christmas message to Earth – “… and the Earth was without form, and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep…” – was their way of sharing the new questions that this perspective urges. As Lovell put it in an interview this year:

But suddenly, when you get out there and see the Earth as it really is, and when you realise that the Earth is only one of nine planets and it’s a mere speck in the Milky Way galaxy, and it’s lost to oblivion in the universe — I mean, we’re a nothing as far as the universe goes, or even our galaxy. So, you have to say, ‘Gee, how did I get here? Why am I here?’

The 20th century realisation of Scipio’s first century BC vision also energised the early stirrings of the environmental movement. When we have seen the fragility and unique compactness of our home in the universe, we know that we have one duty of care, and just one chance.

Space is the destiny of our imagination, and always has been, but Earth is our precious dwelling place. Cicero’s Dream, as well as its realisation in 1968, remind the world, fresh from the Poland climate talks, that what we do with our dreams today will affect generations to come.

Tom McLeish, Professor of Natural Philosophy in the Department of Physics, University of York

Wednesday, December 19, 2018

Why is There Something Rather Than Nothing

BY MICHAEL SHERMER

In my many debates with theists over the decades a handful of arguments for God’s existence are routinely articulated as “proofs” of divine providence. These include the cosmological argument (that all natural things are contingent on something else for their existence so there necessarily exists a being independent of nature), the ontological argument (that we can conceive of an absolutely perfect being means it must exist because existence is a necessary feature of perfection), the design argument (the universe is fine-tuned for life, and life contains design features, therefore God is the fine-tuner and intelligent designer of life), the moral argument (without God anything goes, with God there is objective morality), the consciousness argument (the qualitative experience—qualia—of consciousness cannot be explained by the activity of neurons, and abstract concepts like logic and mathematics exist separate from brains, therefore God must be the source), and others.

All of these arguments (they are certainly not proofs in the mathematical sense) have counter-arguments made by philosophers over the centuries, but there is one that seems to trouble a great many thinkers of all persuasions, and that is why there should be anything at all. That is, all of the other arguments for God’s existence presume that something exists that needs explaining. The argument that asks why there is something rather than nothing underlies all the other arguments, and is cognitively challenging because it is simply not possible for existing beings to imagine not existing, not just themselves (which forms the cognitive foundation of afterlife beliefs), but to imagine nothing existing at all. Go ahead and try it. Picture nothing. When I ask myself this question I start by visualizing dark empty space bereft of galaxies, stars, and planets, along with molecules and atoms. But this picture is incorrect because if there were no universe there would not only be no matter, but there would be no space or time (or space-time) either. There would be absolutely nothing, including no conscious being to observe the nothingness. Just… nothing. Whatever that is.

This presents us with what is arguably the deepest of deep questions: why is there something rather than nothing? In his 1988 blockbuster book A Brief History of Time, the late Cambridge theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking put it this way:

What is it that breathes fire into the equations and makes a universe for them to describe? The usual approach of science of constructing a mathematical model cannot answer the questions of why there should be a universe for the model to describe. Why does the universe go to all the bother of existing?1

Even if it could be established that something must exist, this does not necessarily mean that the something must be our universe with our particular laws of nature that give rise to atoms, stars, planets, and people. There could be universes whose laws of nature permit time and space but no matter or light; such universes could not be perceived because there would be no one to perceive the darkness. Our universe has particular properties suited to planets and people. According to England’s Astronomer Royal Sir Martin Rees, there are at least six constituents that are necessary for “our emergence from a simple Big Bang,” including (1) Ω (omega), the amount of matter in the universe = 1: if Ω was greater than 1 it would have collapsed long ago and if Ω was less than 1 no galaxies would have formed. (2) ε (epsilon), how firmly atomic nuclei bind together = .007: if ε were even fractionally different matter could not exist. (3) D, the number of dimensions in which we live = 3. (4) N, the ratio of the strength of electromagnetism to that of gravity = 1039: if N were smaller the universe would be either too young or too small for life to form. (5) Q, the fabric of the universe = 1/100,000: if Q were smaller the universe would be featureless and if Q were larger the universe would be dominated by giant black holes. (6) λ (lambda), the cosmological constant, or “antigravity” force that is causing the universe to expand at an accelerating rate = 0.7: if λ were larger it would have prevented stars and galaxies from forming.2 […]

READ THE COMPLETE ARTICLE

In my many debates with theists over the decades a handful of arguments for God’s existence are routinely articulated as “proofs” of divine providence. These include the cosmological argument (that all natural things are contingent on something else for their existence so there necessarily exists a being independent of nature), the ontological argument (that we can conceive of an absolutely perfect being means it must exist because existence is a necessary feature of perfection), the design argument (the universe is fine-tuned for life, and life contains design features, therefore God is the fine-tuner and intelligent designer of life), the moral argument (without God anything goes, with God there is objective morality), the consciousness argument (the qualitative experience—qualia—of consciousness cannot be explained by the activity of neurons, and abstract concepts like logic and mathematics exist separate from brains, therefore God must be the source), and others.

All of these arguments (they are certainly not proofs in the mathematical sense) have counter-arguments made by philosophers over the centuries, but there is one that seems to trouble a great many thinkers of all persuasions, and that is why there should be anything at all. That is, all of the other arguments for God’s existence presume that something exists that needs explaining. The argument that asks why there is something rather than nothing underlies all the other arguments, and is cognitively challenging because it is simply not possible for existing beings to imagine not existing, not just themselves (which forms the cognitive foundation of afterlife beliefs), but to imagine nothing existing at all. Go ahead and try it. Picture nothing. When I ask myself this question I start by visualizing dark empty space bereft of galaxies, stars, and planets, along with molecules and atoms. But this picture is incorrect because if there were no universe there would not only be no matter, but there would be no space or time (or space-time) either. There would be absolutely nothing, including no conscious being to observe the nothingness. Just… nothing. Whatever that is.

This presents us with what is arguably the deepest of deep questions: why is there something rather than nothing? In his 1988 blockbuster book A Brief History of Time, the late Cambridge theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking put it this way:

What is it that breathes fire into the equations and makes a universe for them to describe? The usual approach of science of constructing a mathematical model cannot answer the questions of why there should be a universe for the model to describe. Why does the universe go to all the bother of existing?1

Even if it could be established that something must exist, this does not necessarily mean that the something must be our universe with our particular laws of nature that give rise to atoms, stars, planets, and people. There could be universes whose laws of nature permit time and space but no matter or light; such universes could not be perceived because there would be no one to perceive the darkness. Our universe has particular properties suited to planets and people. According to England’s Astronomer Royal Sir Martin Rees, there are at least six constituents that are necessary for “our emergence from a simple Big Bang,” including (1) Ω (omega), the amount of matter in the universe = 1: if Ω was greater than 1 it would have collapsed long ago and if Ω was less than 1 no galaxies would have formed. (2) ε (epsilon), how firmly atomic nuclei bind together = .007: if ε were even fractionally different matter could not exist. (3) D, the number of dimensions in which we live = 3. (4) N, the ratio of the strength of electromagnetism to that of gravity = 1039: if N were smaller the universe would be either too young or too small for life to form. (5) Q, the fabric of the universe = 1/100,000: if Q were smaller the universe would be featureless and if Q were larger the universe would be dominated by giant black holes. (6) λ (lambda), the cosmological constant, or “antigravity” force that is causing the universe to expand at an accelerating rate = 0.7: if λ were larger it would have prevented stars and galaxies from forming.2 […]

READ THE COMPLETE ARTICLE

Skeptic magazine 23.4(2018)

Tuesday, December 18, 2018

Alan Lightman searching for stars

“Maybe the moment is all there is. Maybe I should just gather my clamshells and be quiet. The exquisite experience of joy—when I am completely consumed by a pleasurable activity such as conversation with good friends or good food or laughing with my children—is certainly one of the moment. But for some reason, I and many of my fellow travelers are not satisfied with the moment. The Now isn’t enough. We want to go beyond the moment. We want to build systems and patterns and memories that connect moment to moment to eternity. We long to be part of the Infinite.”

“As far as I know, all major religions that subscribe to a belief in God—including Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism—believe that the universe was created by God at a finite time in the past. The one major contemporary religious tradition that does not incorporate God, Buddhism, holds that the universe has existed for all of eternity. Looked at another way, a universe with a beginning must have had a creation, either by a divine being or by quantum physics. But a universe that has existed forever needs neither.”

“As far as I know, all major religions that subscribe to a belief in God—including Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism—believe that the universe was created by God at a finite time in the past. The one major contemporary religious tradition that does not incorporate God, Buddhism, holds that the universe has existed for all of eternity. Looked at another way, a universe with a beginning must have had a creation, either by a divine being or by quantum physics. But a universe that has existed forever needs neither.”

“It may be that quantum physics can produce a universe from nothing, without cause, but such an accidental and unanalyzable origin for EVERYTHING seems deeply unsatisfying, at least to this pilgrim. In the absence of God, we still want causes and reasons. We still need to make sense of this strange cosmos we find ourselves in. Permanent or impermanent, absolute or relative, we still long for answers, and understanding. Evidently, science can find reasons and causes for everything in the physical universe but not for the universe itself. What caused the universe to come into being? Why is there something rather than nothing? We don’t know and will almost certainly never know. And so this most profound question, although in tightest embrace with the physical world, will likely remain in the domain of philosophy and religion.”

― Alan Lightman, Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine

“As far as I know, all major religions that subscribe to a belief in God—including Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism—believe that the universe was created by God at a finite time in the past. The one major contemporary religious tradition that does not incorporate God, Buddhism, holds that the universe has existed for all of eternity. Looked at another way, a universe with a beginning must have had a creation, either by a divine being or by quantum physics. But a universe that has existed forever needs neither.”

“As far as I know, all major religions that subscribe to a belief in God—including Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism—believe that the universe was created by God at a finite time in the past. The one major contemporary religious tradition that does not incorporate God, Buddhism, holds that the universe has existed for all of eternity. Looked at another way, a universe with a beginning must have had a creation, either by a divine being or by quantum physics. But a universe that has existed forever needs neither.” “It may be that quantum physics can produce a universe from nothing, without cause, but such an accidental and unanalyzable origin for EVERYTHING seems deeply unsatisfying, at least to this pilgrim. In the absence of God, we still want causes and reasons. We still need to make sense of this strange cosmos we find ourselves in. Permanent or impermanent, absolute or relative, we still long for answers, and understanding. Evidently, science can find reasons and causes for everything in the physical universe but not for the universe itself. What caused the universe to come into being? Why is there something rather than nothing? We don’t know and will almost certainly never know. And so this most profound question, although in tightest embrace with the physical world, will likely remain in the domain of philosophy and religion.”

― Alan Lightman, Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine

Wednesday, December 12, 2018

Good enough

Posted for Chase McCullough

John Lachs: "Why Is Good Enough Not Good Enough for Us?"

youtu.be

Watch video of Vanderbilt University Centennial Professor of Philosophy John Lachs on Feb. 23 kick-off a new series of talks that aims to make philosophy acc...

On John Lachs:

This is only peripherally related to the material we covered in class this semester, but I think this lecture is a great example of the genius of John Lachs. It is often said that "perfect is the enemy of the good." However, I never really understood the true power of this statement until I became familiar with Lachs. Here he eloquently describes the philosophical basis of this argument. I think that if we understood why “good enough” is the best alternative to the futile pursuit of “perfection,” we as a society would make progress faster than if we continue to waste energy striving for the elusive and unachievable notion of perfection. I believe that we are only here on earth for a finite amount of time and that time should be used wisely. If we apply this philosophy to every area of our life the time savings could be incredible.

John Lachs: "Why Is Good Enough Not Good Enough for Us?"

youtu.be

Watch video of Vanderbilt University Centennial Professor of Philosophy John Lachs on Feb. 23 kick-off a new series of talks that aims to make philosophy acc...

On John Lachs:

This is only peripherally related to the material we covered in class this semester, but I think this lecture is a great example of the genius of John Lachs. It is often said that "perfect is the enemy of the good." However, I never really understood the true power of this statement until I became familiar with Lachs. Here he eloquently describes the philosophical basis of this argument. I think that if we understood why “good enough” is the best alternative to the futile pursuit of “perfection,” we as a society would make progress faster than if we continue to waste energy striving for the elusive and unachievable notion of perfection. I believe that we are only here on earth for a finite amount of time and that time should be used wisely. If we apply this philosophy to every area of our life the time savings could be incredible.

Sunday, December 9, 2018

Walking

Posted for Melany Rivera (H2)

Walking is always an interesting subject to talk about, yet most do not read on the subject about it. The book I choose for the Final Report is “A Philosophy of Walking” by Frederick Gros. His concepts in this book often lack evidence behind them or theories, but Gros is really invested in what he presents to the world through his work. He believes walking allows us time to play with ideas, explore concepts, and be wrong in our thinking without worrying about others “seeing the rawness of our thoughts”. Which is an interesting concept to me because whenever I have a troubled mind, I walk to find answers so that I can find someone to comprehend my thoughts instead of worrying about what everyone else thinks. In this book, Gros also explores many philosophers and how their lives was shaped by walking. The first words proclaimed in the book is Walking is not a sport. Putting one foot in front of the other is child’s play. However, it has been brought to my attention that at one point , walking was a sport. Throughout this book, each chapter was it’s own thing that includes topics such as freedom, speed, solitude, etc. Each section of titles unpack philosophical aspects of walking. Let’s start with freedom. Freedom can include throwing off one’s burden of cares and just forget business for a time by walking. Gros claims, “Only walking manages to free us from our illusions about the world” Which is weird to me because there are multiple ways to free ourselves such as sleeping. He follows up that sentence with the statement, “By walking you are not going to meet yourself, by walking, you escape from the very idea of identity, the temptation to be someone, to have a name and a history” This goes hand in hand with Rebecca Solnit’s book about having a blank mind while walking because your soul and body has become one. Next concept is speed. Speed is important in walking because you do not want to tire yourself out before arriving at a destination. Gros proclaims that many people think that walking fast is key, we’re driven to get from point A to point B and we need to get there as quickly as possible, this is not leisure, not is it restful. Which is true because within the rush to get to each destination, it can force one to focus on catching your breath instead of deep philosophical questions. Which goes with the next topic of solitude. He claims that walking in groups forces one to jostle, hamper, walk at wrong speed for others. Number one rule for this book is walking is best alone. However, most of the time, this is correct but for a peripatetic class and discussion, this does not fit the criteria. To summarize the rest of the book, it can be said as walking is understood as a means of personal freedom that leads to a joy, happiness, or serenity. It is a short book and I would definitely refer this book to anyone to understand the true meaning of walking.

Walking is always an interesting subject to talk about, yet most do not read on the subject about it. The book I choose for the Final Report is “A Philosophy of Walking” by Frederick Gros. His concepts in this book often lack evidence behind them or theories, but Gros is really invested in what he presents to the world through his work. He believes walking allows us time to play with ideas, explore concepts, and be wrong in our thinking without worrying about others “seeing the rawness of our thoughts”. Which is an interesting concept to me because whenever I have a troubled mind, I walk to find answers so that I can find someone to comprehend my thoughts instead of worrying about what everyone else thinks. In this book, Gros also explores many philosophers and how their lives was shaped by walking. The first words proclaimed in the book is Walking is not a sport. Putting one foot in front of the other is child’s play. However, it has been brought to my attention that at one point , walking was a sport. Throughout this book, each chapter was it’s own thing that includes topics such as freedom, speed, solitude, etc. Each section of titles unpack philosophical aspects of walking. Let’s start with freedom. Freedom can include throwing off one’s burden of cares and just forget business for a time by walking. Gros claims, “Only walking manages to free us from our illusions about the world” Which is weird to me because there are multiple ways to free ourselves such as sleeping. He follows up that sentence with the statement, “By walking you are not going to meet yourself, by walking, you escape from the very idea of identity, the temptation to be someone, to have a name and a history” This goes hand in hand with Rebecca Solnit’s book about having a blank mind while walking because your soul and body has become one. Next concept is speed. Speed is important in walking because you do not want to tire yourself out before arriving at a destination. Gros proclaims that many people think that walking fast is key, we’re driven to get from point A to point B and we need to get there as quickly as possible, this is not leisure, not is it restful. Which is true because within the rush to get to each destination, it can force one to focus on catching your breath instead of deep philosophical questions. Which goes with the next topic of solitude. He claims that walking in groups forces one to jostle, hamper, walk at wrong speed for others. Number one rule for this book is walking is best alone. However, most of the time, this is correct but for a peripatetic class and discussion, this does not fit the criteria. To summarize the rest of the book, it can be said as walking is understood as a means of personal freedom that leads to a joy, happiness, or serenity. It is a short book and I would definitely refer this book to anyone to understand the true meaning of walking.

Saturday, December 8, 2018

Thoreau's Civil Disobedience

Posted for Amber Molder (H3) [images not preserved]

Henry David Thoreau: Civil Disobedience

https://docs.google.com/document/d/15LwbUQTCtBT85JbGbNMR-aunCf1yfVloNbgJXT7HTzg/edit?usp=sharing

Civil Disobedience is an essay that was written by Henry David Thoreau in 1846. It

speaks out against the injustices of the government, and how citizens should respond to them. To

give some insight on what prompted Thoreau to write the essay, you must know the background.

In 1846 the United States declared war on Mexico. Thoreau viewed it as the South's

attempt to expand slavery. The U.S. national law during that time stated that slaves attempting to

escape slavery must be returned to their owner, even if found in free states. Thoreau opposed

slavery, and as an act of protest he refused to pay his taxes. He was arrested in July 1846 for tax

delinquency and had to spend a night in jail (it was supposed to be more than one night, but

historians believe it was a relative that bailed him out). Thoreau being put in jail prompted him to

write the essay “Civil Disobedience”.

● The essay was originally published as

“Resistance to Civil Government” in

1849.

● Also referred to as “On the Duty of

Civil Disobedience” in early 1900’s.

● The school of Life has a great video

that highlights the main cause of and

points in the essay. Here’s a link!

https://youtu.be/gugnXTN6-D4 .

Thoreau begins the essay by stating “That government is best which governs least”. He

urges people to not follow the majority, if their conscience tells them it is wrong. Thoreau

declares that a man of conscience must act against injustices from the government. Thoreau

states the petitioning and voting for reform within institutions like the government would make

little change. Instead, he suggests disassociating from them.

● “A person is not obligated to devote

his life to eliminating evils from the

world, but he is obligated not to

participate in such evils.”

● Thoreau states that people should

“break the law” if the government

required people to obey “unjust

laws”.

He argued that the government must earn the right to collect taxes from its citizens.

While the government commits unjust actions, conscientious individuals must choose or refuse

to pay their taxes. Thoreau (as I mentioned earlier), refused to pay his taxes because he knew the

money would be funding the war and slavery and he wanted no part of it.

He entered Concord, Massachusetts one morning to get his shoes repaired, when he was

arrested for tax delinquency. Thoreau was not afraid of spending some time behind bars.

“Under a government

which imprisons any

unjustly,” he states, “the

true place for a just man is

also a prison.”

Symbolically the essay suggests to follow your inner morale and conscience, before

following a government. If the Government is doing unjust things, we must speak out and act out

against it. We must not be bystanders and allow immoral laws to stand.

Sources:

https://youtu.be/gugnXTN6-D4

http://www.sparknotes.com/philosophy/civildisobedience/summary/

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/civil-disobedience/

http://www.sparknotes.com/philosophy/civildisobedience/context/

____________________________________________________________________________

Here is a link to my Midterm Blogpost : https://docs.google.com/document/d/1XPohPyc

JI86kU3-v0OW5V7hrVL2-G37UTcEvInLv4C8/edit?usp=sharing .

I tried to commented on Cami Farr and Camden Welch’s final blogs. The website wouldn’t let

me publish my comments (https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0?ui=2&ik=320843e8fa&attid=0.

1&permmsgid=msg-a:s:-679056341990839995&th=16784a46ab7913f4&view=att&disp=safe&r

ealattid=c35de853db126586_0.1). Copying below what I intended on posting.

1. Cami’s Blog (Link: https://cophilosophy.blogspot.com/2018/12/short-sweet-and-to-

point-truth-to.html) Amber Molder H-03// I find my outlook on life somewhere right

between Cottingham and Arieff. I know that life is not a set number of days, any one in

particular could be the last. I agree with Cottingham on trying to make it count, by getting

out there, conquering the day, and having fun. We are always so busy (especially as

college students) but we shouldn't give up opportunities to do new things, even the things

that may scare us. Better to try things and be spontaneous then live with "what ifs".

2. Camden’s Blog (Link: https://cophilosophy.blogspot.com/2018/12/the-truman-show-is-

real-better.html) Amber Molder H-03// I think we are all guilty of living in filtered lives

from time to time. We get wrapped up in our personal problems, stresses, goals, work,

etc. I think as long as you can take a step back and realize these issues are temporary and

only present if we allow ourselves to be bothered by them then we are still living in true

reality. Work, school, stress hobbies, they are all self imposed. If an individual is not

happy with how their life is going then they have the right and the power to change it.

Don’t live life unhappy by doing things you are “suppose to be doing”.

____________________________________________________________________________

Henry David Thoreau: Civil Disobedience

https://docs.google.com/document/d/15LwbUQTCtBT85JbGbNMR-aunCf1yfVloNbgJXT7HTzg/edit?usp=sharing

Civil Disobedience is an essay that was written by Henry David Thoreau in 1846. It

speaks out against the injustices of the government, and how citizens should respond to them. To

give some insight on what prompted Thoreau to write the essay, you must know the background.

In 1846 the United States declared war on Mexico. Thoreau viewed it as the South's

attempt to expand slavery. The U.S. national law during that time stated that slaves attempting to

escape slavery must be returned to their owner, even if found in free states. Thoreau opposed

slavery, and as an act of protest he refused to pay his taxes. He was arrested in July 1846 for tax

delinquency and had to spend a night in jail (it was supposed to be more than one night, but

historians believe it was a relative that bailed him out). Thoreau being put in jail prompted him to

write the essay “Civil Disobedience”.

● The essay was originally published as

“Resistance to Civil Government” in

1849.

● Also referred to as “On the Duty of

Civil Disobedience” in early 1900’s.

● The school of Life has a great video

that highlights the main cause of and

points in the essay. Here’s a link!

https://youtu.be/gugnXTN6-D4 .

Thoreau begins the essay by stating “That government is best which governs least”. He

urges people to not follow the majority, if their conscience tells them it is wrong. Thoreau

declares that a man of conscience must act against injustices from the government. Thoreau

states the petitioning and voting for reform within institutions like the government would make

little change. Instead, he suggests disassociating from them.

● “A person is not obligated to devote

his life to eliminating evils from the

world, but he is obligated not to

participate in such evils.”

● Thoreau states that people should

“break the law” if the government

required people to obey “unjust

laws”.

He argued that the government must earn the right to collect taxes from its citizens.

While the government commits unjust actions, conscientious individuals must choose or refuse

to pay their taxes. Thoreau (as I mentioned earlier), refused to pay his taxes because he knew the

money would be funding the war and slavery and he wanted no part of it.

He entered Concord, Massachusetts one morning to get his shoes repaired, when he was

arrested for tax delinquency. Thoreau was not afraid of spending some time behind bars.

“Under a government

which imprisons any

unjustly,” he states, “the

true place for a just man is

also a prison.”

Symbolically the essay suggests to follow your inner morale and conscience, before

following a government. If the Government is doing unjust things, we must speak out and act out

against it. We must not be bystanders and allow immoral laws to stand.

Sources:

https://youtu.be/gugnXTN6-D4

http://www.sparknotes.com/philosophy/civildisobedience/summary/

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/civil-disobedience/

http://www.sparknotes.com/philosophy/civildisobedience/context/

____________________________________________________________________________

Here is a link to my Midterm Blogpost : https://docs.google.com/document/d/1XPohPyc

JI86kU3-v0OW5V7hrVL2-G37UTcEvInLv4C8/edit?usp=sharing .

I tried to commented on Cami Farr and Camden Welch’s final blogs. The website wouldn’t let

me publish my comments (https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0?ui=2&ik=320843e8fa&attid=0.

1&permmsgid=msg-a:s:-679056341990839995&th=16784a46ab7913f4&view=att&disp=safe&r

ealattid=c35de853db126586_0.1). Copying below what I intended on posting.

1. Cami’s Blog (Link: https://cophilosophy.blogspot.com/2018/12/short-sweet-and-to-

point-truth-to.html) Amber Molder H-03// I find my outlook on life somewhere right

between Cottingham and Arieff. I know that life is not a set number of days, any one in

particular could be the last. I agree with Cottingham on trying to make it count, by getting

out there, conquering the day, and having fun. We are always so busy (especially as

college students) but we shouldn't give up opportunities to do new things, even the things

that may scare us. Better to try things and be spontaneous then live with "what ifs".

2. Camden’s Blog (Link: https://cophilosophy.blogspot.com/2018/12/the-truman-show-is-

real-better.html) Amber Molder H-03// I think we are all guilty of living in filtered lives

from time to time. We get wrapped up in our personal problems, stresses, goals, work,

etc. I think as long as you can take a step back and realize these issues are temporary and

only present if we allow ourselves to be bothered by them then we are still living in true

reality. Work, school, stress hobbies, they are all self imposed. If an individual is not

happy with how their life is going then they have the right and the power to change it.

Don’t live life unhappy by doing things you are “suppose to be doing”.

____________________________________________________________________________

Friday, December 7, 2018

Michel Foucault and The Concept of Normalization

Sarah Barclay - H-03

What Is Normal? How do we define normal in our society? How has the concept of normal changed from 100 years ago? 50 years ago? 20 years ago? Why is it normal?

What Is Normal? How do we define normal in our society? How has the concept of normal changed from 100 years ago? 50 years ago? 20 years ago? Why is it normal?

Philosopher Michel Foucault focused a large amount of time

on the concept of normalization, moving from topics like madness, sexuality,

and prison.

As I mentioned in my midterm blog post, Merlí, the Spanish show about a philosophy teacher, is one of my

favorite shows, and it has introduced me to many philosophers, including Foucault.

During the episode “Foucault,” they talk about the concept of normality which

has always been an interest of mine. Attaching a name to that concept pushed me

to do research and made me want to learn more about Michel Foucault.

Born in 1926 to a family of doctors in Paris, France, Foucault

was raised in a conservative upper-middle-class, bourgeois family. Although he

never really spoke about his childhood, when he did, he recalled his father’s strictness

and punishments he had endured, referring to his father as a bully and himself

more of a delinquent.

Foucault was well educated, earning his baccalaureate (French

diploma allowing for further education at a university) in 1943 before moving

to École Normale Supérieure and the University of Paris. He mainly studied

psychology, its history and philosophy, and was well read in medical and social

sciences.

The Concept of Normalization

Our perception of what’s normal is created by a few societal

influences which in turn has an effect on our behavior towards different things.

Our mood and emotions easily determine how we feel and whether

or not we like something at any given moment. If you have negative feelings

toward something, you’re bound to reject it more than if you had positive

feelings, and vice versa.

Development during childhood has a strong influence on our

ideals and values, especially due to how we’re raised by parents or other

family members. Your belief system is formed by your parents’ belief systems,

and what’s important to them could become important to you, whether you’re

aware of this or not.

Role models form more behavioral effects as you age, and as

you age out of your ability to alter how you think. These are people like

teachers, mentors, celebrities, activists, even philosophers. If you like a

person’s stance on an issue, you might be more inclined to follow more of their

stances, even on things you’ve never thought about before.

In a 1971 televised debate with Noam Chomsky, Foucault

expressed a philosophy similar of that to John Locke where he argued against

the possibility of any fixed human nature. He thought that people were influenced

by their surroundings.

A large part of Foucault’s philosophy surrounded the concept

of normal through his works on madness, sexuality, and prison.

Throughout his life, he wrote a few books on these subjects

• The

History of Madness (1961)

• The

Birth of the Clinic (1963)

• The

Order of Things (1966)

• The

Archaeology of Knowledge (1969)

• Discipline

and Punish (1975)

• The

History of Sexuality (1976)

In 1961, Foucault wrote The

History of Madness (L’Histoire de la

folie), largely influenced by his academic knowledge of psychology and his

work in a Parisian mental hospital, as well as his anger towards the moral

hypocrisy of modern psychiatry. To Foucault, the idea that people who were mentally

ill or sick needed some sort of medical treatment was not an improvement on

earlier treatments and concepts. He thought treatments for the mad were a cover

for controlling them, so they would fall under the conventional bourgeois

morality. Foucault argued that the idea of mental illness was really the result

of questionable social and artificial commitments.

In his book The History

of Sexuality (L’Histoire de la

sexualité), Foucault condemns the idea that western culture had suppressed

sexuality for the past 300 years. Not only that, but he believed that society had

an interest in sexualities with fell outside of the marital “normality,” like children,

the mentally ill, the criminal and homosexual. Due to his thoughts and opinions

expressed within this book, Foucault is credited with the idea that sexuality,

including homosexuality, is a social construct. Basically, the only thing that

made it taboo was the society at the time that viewed it and the ideals that

were passed down through that society.

Foucault is arguably most known for his thoughts on prison,

especially with its influence on modern society. In 1975, his book Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the

Prison (Surveiller et punir:

Naissance de la prison) was published. This was genealogical study of the

development of the supposedly “better, nicer,” more modern way of imprisonment,

rather than the old way of torture or death sentences. With this study,

Foucault claimed that this newer prison system was a better way of being able

to gain more control. He argued that this new form of punishment was a model

for controlling an entire society, with some of the systems being integrated

into things like factories, hospitals, and schools. If you remember TCAP testing,

the ACT/SAT in schools, or wellness tests in hospitals, Foucault saw these as

methods of gaining control. He thought this standardization was a way to

combine hierarchical observation with normalizing judgment. The people passing

judgment are able to see a large amount of information on any one person and

Foucault felt that they could/would use that information for the power system’s

benefit and increase their ability to control that person.

Along with those standards, Foucault thought that if you

tried to deviate, you’d fall into a different set of standards and would never be

able to be free.

Quiz

- What is one of Foucault’s works?

- Name one factor of how someone can be influenced in society?

- How did Foucault view the treatment of madness?

- Who did Foucault debate in 1971?

Discussion Questions

- What makes something normal? Why is or should something be considered normal?

- In a society that hates your true self or finds you abnormal, would you find it easier to express your yourself the way you are or to change yourself into someone deemed appropriate/normal?

For more on Foucault

Midterm Report: Epicurus

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)