I can remember as a very young child asking the question, “How does a baby learn to speak?” I wasn’t really satisfied with the answer my mother gave me – that you just point to things and say their names. I’m not sure I could answer the question now, but it was certainly of philosophical interest. As a teenager, I also picked out Bertrand Russell’s History of Western Philosophy from the local public library, which was one of the great inspirations for me. The library, that is, rather than the book. I think it’s the route out of suburbia for a lot of people. It opened up different sorts of reading for me. I would walk several miles to the local library and take out as many books as I could. Inevitably, sooner or later I got some philosophy books, along with all sorts of weird and wonderful ones.

What did you make of the Russell book?

It wasn’t the book I needed at that age. I’ve since tried to write that book a couple of times, but I don’t know if I’ve succeeded. It was a bit slow-moving for me and I didn’t get beyond the pre-Socratics, who didn’t really stimulate me.

So did you really get into the subject at university?

I actually went to Bristol University to study psychology, but I became a bit disillusioned with it and dropped out. After a year out from university, that I mostly spent working as a car park attendant, the decisive factor for me about going back to university to study philosophy rather than psychology was that there was a clash between the two courses. I was very interested in reading Sartre and I wouldn’t have been able to study Sartre’s Being and Nothingness in psychology. That clash made me realise how much I wanted to understand that book, or at least parts of it. That was my one opportunity, I felt, because it isn’t the kind of book you can make sense of on your own. So I switched to philosophy.

It seems a lot of Anglo-American philosophers are drawn into the subject as teenagers by their encounters with existentialism, and especially Sartre. But often, after a certain number of years of study, they come to strongly disagree with Sartre’s philosophy. Did that happen to you?

I don’t think you have to agree with the philosophers you read. It’s almost better if you disagree with them because then you have some kind of dialogue – you don’t read them in a passive way. I find Sartre stimulating, difficult and frustrating. His later writings are unreadable, driven by his use of the drug speed and written with no concessions to the reader. So the fact that I disagree with huge amounts of what Sartre said doesn’t mean that he wasn’t an amazing and important thinker to me.

Sartre was also a novelist, and his novels are often described as philosophical. Do you think novels and novelists can really engage in philosophy, or is that only possible if you’re a professional academic philosopher?

I think professional philosophers often like to make their subject smaller than it really is by setting arbitrary limits. As far as I’m concerned, philosophy is any human enterprise that involves critical thought about basic questions, like how we should live, what is the nature of reality and so on. Those questions can be asked seriously in all kinds of forms. So I don’t see the subject as restricted to nerdy philosophical papers in refereed journals. Some of the most important contributions have been literary. If you think of classical philosophy, you have Plato’s very literary dialogues, and Lucretius’s On The Nature of Things is a poem! Some parts of TS Eliot’s poems are very philosophical. Kierkegaard is a poetic writer who uses fictions, and Nietzsche uses aphorisms and poetry. They’re all philosophers.

Do you think, given the success of your podcast series Philosophy Bites, that there has been increased interest in philosophy over the past 30 years?

There may have been the same appetite for philosophy back then, but it wasn’t necessarily filled in a palatable way. When I began writing introductory philosophy books in the late 1980s, the only introductions that were readily available were The Problems of Philosophy by Bertrand Russell, which was published in 1912, and a book called Philosophy MadeSimple – which was actually a good book, but people found the title off-putting because it sounded like it was dumbing the subject down. If you go into a bookshop now there would be a whole bookcase of introductory books, but 20 years ago there were surprisingly few philosophy books designed for the general reader.

When I was teaching A level [high school] philosophy students and undergraduates, I was aware that there were no books to help people make the transition from an interest in philosophy to being able to read some of the classics. So I wrote a book called Philosophy: The Basics. Most university teachers would say you don’t really need an introduction, you can just go and read Hume or Descartes or Mill. But many readers can’t get through that sort of writing and gain an overview of the key points without a bit of help.

Let’s talk about your first choice, What Does It All Mean? by Thomas Nagel.

I just dug through my bookshelves looking for this but I couldn’t find it. I’ve had a number of copies of this book but I always seem to end up giving it away, which I think is a good sign.

Why is it such a good gateway into the subject?

It’s perfect for someone who wants to find out what philosophy is all about. First of all, it’s very, very short. Secondly, it’s written in prose that is completely unpretentious, unpatronising and clear. It’s the kind of book you could read in an evening, but at the same time you’d really have a flavour of what philosophy is. It’s got the authority of him being a significant philosopher in his own right, but if you had no idea who he was it wouldn’t matter. The writing is almost Orwellian in its simplicity and directness. As somebody who has tried to write clear introductory books, I know how difficult that is to pull off.

Nagel begins with the observation – which mirrors my experience as a teacher and as a father – that philosophy arises naturally out of the human condition. People start asking philosophical questions from an early age. And there is a history of over 2,000 years of people discussing these questions – thinking critically about how we should live, what the nature of reality is, what consciousness is. Nagel goes through all these major areas of philosophy with a very light touch.

“What does it all mean?” is a question that people who haven’t studied philosophy often think the subject is about. They might be a little disappointed, if they study it formally, to discover that there is little talk about the meaning of life and so on. Do you think the title might give readers false expectations?

In the introduction to the book, Nagel writes, “There isn’t much you can assume or take for granted. So philosophy is a somewhat dizzying activity, and few of its results go unchallenged for long.” He’s not pretending philosophy is going to tell you what it all means. It’s going to introduce you to the questions and help you think critically about them. If somebody comes to philosophy thinking they are going to come out after a few years understanding exactly how we should live and what reality is like, then they’re naive. That’s one of the things you learn from studying philosophy. As Socrates pointed out, true wisdom lies in knowing how little you know.

Read

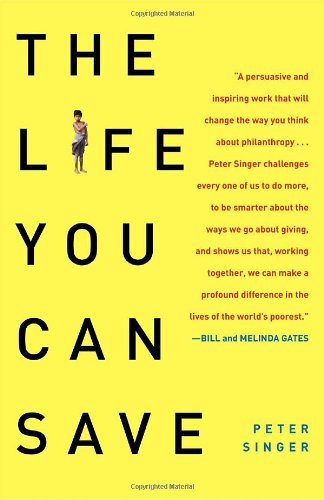

The next book is The Life You Can Save by Peter Singer, who is perhaps the most famous living philosopher.

I was thinking, “How would you introduce philosophy to someone who didn’t know anything about it?” I think the central question in philosophy is, “How should we live?” And that’s a question about which Peter Singer has a lot to say.

What is the central message of the book?

The book focuses on the terrible poverty and disease found around the world, and how we in the West are living in a luxury that we could adjust just a little bit in order to alleviate that misery. He suggests that we give maybe 5% of our wages to charity. He’s not saying you have to live in a sackcloth and give away all your possessions. Even a small gift of 5% would make a tremendous difference to other people’s lives. It’s not just him preaching, he gives arguments for his positions. And even if you disagree with him, the process of reading his work makes you think, “Why do I disagree?” He is in the tradition of Socrates – somebody who challenges your preconceptions and asks you to respond.

How does the book begin?

Singer starts with a compelling thought experiment. Imagine you’re passing a pond. There’s a young child drowning in the pond and his head’s just about to go underwater. You’re on your way to work, you’re nicely dressed. But you’d surely jump in the pond and try to save the child, wouldn’t you? Almost anyone would do that unthinkingly, even though it would ruin their expensive clothes and make them late for work. Yet in our everyday lives, we know that through inaction we are allowing children to die of poverty who could otherwise be saved by a minimal contribution – less than the price of an expensive pair of shoes.

What’s the difference between the situation described in the thought experiment and our inaction in everyday life? Singer thinks that there isn’t an important moral difference. He says there are ways in which we could act that would be the equivalent of saving the drowning child’s life – giving to charities that tackle poverty, disease and so on. He believes most of us could be much more generous at very little cost to our own lives, and that the result of this would be of huge measurable benefit to mankind.

That sounds like a persuasive argument in theory. What are the objections?

Singer is brilliant because you don’t have to agree with him, but he goes through all the standard objections to his view and presents counterarguments. Someone might say, “The difference is that if I save the child myself I know the child is going to be saved, but if I give my money to a charity it might be wasted.” Well, there’s a website that has been set up which analyses the comparative effects of money sent to different charities. It comes up with charities where the effect of your donation is most likely to save lives. So Singer has second-guessed you, and come up with a counterargument and a practical way of implementing the conclusion he’d like you to embrace.

What do you think of Singer’s work more generally?

Singer is incredibly consistent in his positions. He used to be a chess player, but he believes that the point of philosophy is not to solve chess-like problems but actually to make a difference. If you really believe, as he does, in a form of utilitarianism – the view that the consequences of our actions determine their rightness or wrongness – then that’s not just an intellectual position, it should affect how you live. Singer is a counter-example to the stereotype of the philosopher in an ivory tower, whose life makes no difference, who leaves everything as it is.

(continues)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.