To Chap's "too much information" response to Don's sharing of Peirce's "How to Make Our Ideas Clear," I suggested that A Little History of Philosophy has everything you need to know about him. That was an overstatement. But you can glean plenty of helpful info from it, and from the online Philosophy Pages. For instance:

Charles Sanders Peirce

(1839-1914)Life and Works

. . Belief

. . Reality

. . Pragmatism

Bibliography

Internet Sources- Charles Sanders Peirce studied philosophy and chemistry at Harvard, where his father, Benjamin Peirce, was professor of mathematics and astronomy. Although he showed early signs of great genius, an unstable personal life prevented Peirce from fulfilling his early promise. He wrote widely and delivered several series of significant lectures, but never completed the most ambitious of his philosophical projects. After a respectable scientific career studying the effects of gravitation with the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, Peirce taught logic and philosophy for five years at Johns Hopkins University. In 1887, however, he retired to a life of isolation, poverty, and illness in Milford, Pennsylvania.

Peirce's early philosophical development relied on a Kantian theory of judgment, but careful study of the logic of relations led him to abandon syllogistic methods in favor of the study of language and belief. His place as the founder of American pragmatism was secured by a pair of highly original essays that apply logical and scientific principles to philosophical method. In The Fixation of Belief (1877) Peirce described how human beings converge upon a true opinion, each of us removing the irritation of doubt by forming beliefs from which successful habits of action may be derived. This theory was extended in How to Make Our Ideas Clear (1878) to the very meaning of concepts, which Peirce identified with the practical effects that would follow from our adoption of them.

Peirce's early philosophical development relied on a Kantian theory of judgment, but careful study of the logic of relations led him to abandon syllogistic methods in favor of the study of language and belief. His place as the founder of American pragmatism was secured by a pair of highly original essays that apply logical and scientific principles to philosophical method. In The Fixation of Belief (1877) Peirce described how human beings converge upon a true opinion, each of us removing the irritation of doubt by forming beliefs from which successful habits of action may be derived. This theory was extended in How to Make Our Ideas Clear (1878) to the very meaning of concepts, which Peirce identified with the practical effects that would follow from our adoption of them. In his extensive logical studies, Peirce developed a theory of signification that anticipated many features of modern semiotics, emphasizing the role of the interpreting subject. To the traditional logic of deduction and induction, Peirce added explicit acknowledgement of abduction as a preliminary stage in productive human inquiry. Continuing to defend a Kantian system of categories, Peirce proposed a descriptive metaphysics that presumed the reality of external referents for our sensations.

In his extensive logical studies, Peirce developed a theory of signification that anticipated many features of modern semiotics, emphasizing the role of the interpreting subject. To the traditional logic of deduction and induction, Peirce added explicit acknowledgement of abduction as a preliminary stage in productive human inquiry. Continuing to defend a Kantian system of categories, Peirce proposed a descriptive metaphysics that presumed the reality of external referents for our sensations.

| Recommended Reading:

Primary sources:

Secondary sources:

Additional on-line information about Peirce includes:

|

Here's the old post about my colleague and Peirce, referenced in my reply to Don's comment below. This is from 2012.

Clarify, clarify

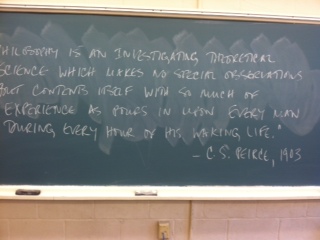

Every Opening Day every semester, it seems, I follow my colleague Mary into James Union Building Room 304 and find this on the board:

That’s Charles Sanders Peirce, the “pragmaticist” (“ugly enough to be safe from kidnappers”). In case you find either Mary or CSP (or both) difficult to decipher, here’s what he said… followed by what I think of what he said:

Philosophy is that branch of positive science (i.e., an investigating theoretical science which inquires what is the fact, in contradistinction to pure mathematics which merely seeks to know what follows from certain hypotheses) which makes no observations but contents itself with so much of experience as pours in upon every man during every hour of his waking life. CSP

I think Charles & Mary are on the right track, to call attention to everyday experience as the raw material of philosophy. Quotidian, commonplace, ordinary experiences and exceptional, rare, out-of-the-ordinary experiences happen to people. What has existence must have its reflective moment.

But, must philosophy aspire to the status of a science? I say no. (Think of Emerson, or for that matter Emily Dickinson.) This may just be a semantic hairsplitting, depending on how much of the vast range of possible-plus-actual experience the “scientific philosopher” is prepared to reflect on, and how much she is prepared to jettison in the name of positivity.

My view: there are many diverse and legitimate forms of philosophical reflection. Some look less like science than like poetry. They all have their place.

And maybe Peirce thought so too. He definitely had his poetic/metaphysical flights: agapism, cosmic love, firstness and secondness and thirdness, his metaphorical likening of philosophy to an impassioned marriage (“The genuis of a man’s logical method should be loved and reverenced as his bride”-Fixation of Belief 1877).

“It will be seen that pragmatism is not a Weltanschauung but is a method of reflexion having for its purpose to render ideas clear.” As James said: philosophy and metaphysics are just an “unusually obstinate attempt to think clearly.”

The consensus here is kind of Thoreauvian, isn’t it? “Simplify, simplify.” And how do you do that, in our discipline? Clarify, clarify. Science can help, and so can the poet.

==

Here's another old post (from 2009) about James's "Walpurgisnacht" experience, which I mentioned yesterday.

Walpurgis Nacht

William James had a very strange experience on this date in 1898. He called it his Walpurgis Nacht. (Walpurgisnacht is the night before May Day, when spirits are said to walk the earth.)

It was a rare “marvelous” mystical moment for James, strange by any account. But stranger still, to me, is the fact that the New York Times recently wrote a story about it and the place where it happened (on Mount Marcy in sight of Mount Haystack and Panther Gorge, in the Adirondacks) called “The Geography of Religious Experience”. It recounts the odd letter James wrote his wife about the episode:

“The moon rose and hung above the scene, leaving a few of the larger stars visible,” he wrote, “and I entered into a state of spiritual alertness of the most vital description. The influences of Nature, the wholesomeness of the people around me… the thought of you and the children … the problem of the Edinburgh lectures [which would become Varieties of Religious Experience], all fermented within me till it became a regular Walpurgis nacht.”

James didn’t have or report many (perhaps any) more mystical experiences of his own, if indeed this counts as one, but he was always willing to credit the testimony of others who did. Or at least, to extend the benefit of the doubt. There’s something very admirable in that, something much finer than a mere credulous “will to make-believe,” in Bertrand Russell’s sneering put-down.

But I wouldn’t call the sort of momentous, amorphous, inexpressible experience he couldn’t find words for but still (like a poet) tried to communicate and point at, a religious experience. It was an experience, thoroughly human and natural (and debilitating, literally heart-rending in this instance). I’ll bet I’d have something like it myself right now, if I went and hiked a mountain. Especially if I’d hiked one the day before yesterday, and the day before that too, as James had. That wouldn’t diminish the exceptionality of it for me, but it ought to make me hesitant to bring supernature into the account. Oughtn’t it?

Mountains and ecstatic philosophizing seemed to go together for James. That’s one thing he had in common with Nietzsche, who admired Emerson’s nature intoxication. You can keep your feet on the ground when your head enters the clouds.

==

And another, from 2010, on James and belief. I don't agree with the assumption that James would endorse this argument. "Flaw 3" is particularly off-target, James never said we should "only consider the pragmatic effects on the believer’s life" and not "the effects on everyone else." But it's still a helpful way to approach about the pragmatics of religious belief.

WJ’s leap

Speaking of Will to Believe, here’s Cass Seltzer’s [Rebecca Goldstein‘s] analysis in 36 Arguments for the Existence of God:

32. The Argument from Pragmatism

(William James’s Leap of Faith)

1. The consequences for the believer’s life of believing should be considered as part of the evidence for the truth of the belief (just as the effectiveness of a scientific theory in its practical applications is considered evidence for the truth of the theory). Call this the pragmatic evidence for the belief.2. Certain beliefs effect a change for the better in the believer’s life — the necessary condition being that they are believed.3. The belief in God is a belief that effects a change for the better in a person’s life.4. If one tries to decide whether or not to believe in God based on the evidence available, one will never get the chance to evaluate the pragmatic evidence for the beneficial consequences of believing in God (from 2 and 3).5. One ought to make ‘the leap of faith’ (the term is James’s) and believe in God, and only then evaluate the evidence (from 1 and 4).

This argument can be read out of William James’s classic essay “The Will to Believe.” The first premise , as presented here, is a little less radical than James’s pragmatic definition of truth in general, according to which a proposition is true if believing that it is true has a cumulative beneficial effect on the believer’s life. The pragmatic definition of truth has severe problems, including possible incoherence: in evaluating the effects of the belief on the believer, we have to know the truth about what those effects are, which forces us to fall back on the old-fashioned notion of truth. To make the best case for The Argument from Pragmatism, therefore, the first premise is here understood as claiming only that the pragmatic consequences of belief are a relevant source of evidence in ascertaining the truth, not that they can actually be equated with the truth.

FLAW 1: What exactly does effecting “a change for the better on the believer’s life” mean? For an antebellum Southerner, there was more to be gained in believing that slavery is morally permissible than in believing it heinous. It often doesn’t pay to be an iconoclast or revolutionary thinker, no matter how much truer your ideas are than the ideas opposing you. It didn’t improve Galileo’s life to believe that the earth moved around the sun rather than that the sun and the heavens revolve around the earth. (Of course, you could say that it’s always intrinsically better to believe something true rather than something false, but then you’re just using the language of the pragmatist to mask a non-pragmatic notion of truth.)

FLAW 2: The Argument from Pragmatism implies an extreme relativism regarding the truth, because the effects of belief differ for different believers. A profligate, impulsive drunkard may have to believe in a primitive retributive God who will send him to Hell if he doesn’t stay out of barroom fights, whereas a contemplative mensch may be better off with an abstract deistic presence who completes his deepest existential world view. But either there is a vengeful God who sends sinners to Hell or there isn’t. If one allows pragmatic consequences to determine truth, then truth becomes relative to the believer, which is incoherent.

FLAW 3: Why should we only consider the pragmatic effects on the believer’s life? What about the effects on everyone else? The history of religious intolerance, including inquisitions, fatwas, and suicide bombers, suggests that the effects on one person’s life of another person’s believing in God can be pretty grim.

FLAW 4: The pragmatic argument for God suffers from the first flaw of The Argument from Decision Theory (#31 above) — namely the assumption that the belief in God is like a faucet that one can turn on and off as the need arises. If I make the leap of faith in order to evaluate the pragmatic consequences of belief, then if those consequences are not so good, can I leap back again to disbelief? Isn’t a leap of faith a one-way maneuver? “The will to believe” is an oxymoron: beliefs are forced on a person (ideally, by logic and evidence); they are not chosen for their consequences.

==

And, an excerpt from William James's "Springs of Delight," on James's general orientation towards religion:

We should say a word more here about the term salvation,

which may mislead with its freighted implications of supernatural

or eternal life. James is certainly aware that many or even most

religious persons in our Western religious traditions are deeply

wedded to belief in the persistence of their own personalities or

"souls" in incorporeal form. He is himself not hostile to such a

belief and sometimes seems to entertain the possibility as what

he would call a "live option," a candidate for his own belief.

Yet, the record seems fairly clear that he remained neutral,

publicly, about the extent or the supernatural status of his own

personal faith. James's frank responses to a questionnaire on

religion in 1904 provide real insight: Do you believe in personal

immortality? "Never keenly; but more strongly as I grow older."

Do you pray? "I cannot possibly prayóI feel foolish and artificial." What do you mean by 'spirituality'? "Susceptibility to ideals, but with a certain freedom to indulge in imagination about them. A certain amount of 'other worldly' fancy. Otherwise you have mere morality, or 'taste.'" What do you mean by a 'religious experience'? "Any moment of life that brings the reality of spiritual things more 'home' to one."4 I know that many will read in these responses a Jamesian tilt toward supernaturalism, but I am more inclined to view them as a nod of sympathetic recognition and moral support, an instance of neutral distancing and what Perry has called his belief in (others') believing. In any case, his use of the term salvation in the present context is neutral with respect to any supernatural implications. It means something like "deliverance from evil," where 'evil' is not taken necessarily to imply a malevolent supernatural agency at work in the world, and where it is hoped and supposed that natural human powers are equal to the task of resisting it successfully, not always but often, at least in the long run.

==Finally (for now) here's a notice about a new lecture series on James:

Title: The Notion of Consciousness According to William James (La Notion de Conscience. A Partir de William James)There will be four lectures, all held at École Normale Supérieure in Paris. Each will be in English, though questions can be in either French or English. Entrance is free, though please email Mathias Girel at mathias.girel@ens.fr if you would like to attend.OVERVIEW of lectures:The American philosopher and scientist William James (1842 – 1910) is sometimes thought to have been a forerunner of behaviorist psychology. As early as 1904, he notoriously argued that consciousness does not exist. Behaviorists would later contend that psychology ought to study the relationship between sensory stimulii and behavioral reaction, with no reference to any intervening conscious state, and some leading advocates of this movement were apparently influenced by James’s earlier, unorthodox view.Today, behaviorism has been firmly rejected, and researchers with a newfound interest in consciousness are looking again at the so-called introspectionist (i.e., pre-behaviorist) era of psychology for clues about how we might use controlled introspection in a genuinely scientific study of subjective mental states. What is surprising is that like some behaviorists, these self-styled consciousness-scientists also cite James as an exemplar of how to do psychology. How can one and the same figure have inspired both the rejection and the embrace of consciousness in psychology ?We can give a superficial answer by pointing out that consciousness scientists are typically inspired not by James’s 1904 argument against consciousness, but by his earlier masterpiece, The Principles of Psychology (1890). But this leaves an obvious problem—it is hard to understand why the psychologist who made such ingenious use of introspection in the Principles might later have come to reject the existence of consciousness altogether.My lectures explore James’s evolving views on consciousness. I critically evaluate an evolutionary account he had offered in his early career, paying special attention to the physiological research from which he drew that initial account. Then I contend that James’s later, apparent rejection of consciousness was a corollary of his earlier work on the nature of sense perception, which I explore in detail as well. It turns out that both early and late in his career, James accepted that to be conscious is to appraise or evaluate what is in one’s environment. In 1904, what he rejected was one specific, prevailing way of thinking about consciousness, a view according to which consciousness is like a container that holds or envelops its contents. I show that by the end of his career, James both rejected a container/content view, and yet still embraced a view of consciousness as an act of environmental evaluation. What is more, I argue that this position is both consistent and compelling.ABSTRACTS for each lecture:Lecture 1: The Curious Case of the Decapitated FrogPhysiologists have long known that some vertebrates can survive for months without a brain. This phenomenon attracted limited attention until the 19th century when a series of experiments on living, decapitated frogs ignited a controversy about consciousness. Pflüger demonstrated that such creatures do not just exhibit reflexes; they also perform purposive behaviors. Suppose one thinks, along with Pflüger’s ally Lewes, that purposive behavior is a mark of consciousness. Then one must count a decapitated frog as conscious. If one rejects this mark, one can avoid saying peculiar things about decapitated animals. But as Huxley showed, this position leads quickly to epiphenomenalism. The dispute long remained stalemated because it rested on conflicting sets of intuitions that were each compatible with the growing body of experiments. Understanding this controversy in physiology is a necessary background to grasping James’s evolutionary account of consciousness.Lecture 2: Consciousness as Caring: James’s Evolutionary HypothesisBetween 1872 and 1890, William James developed a neglected form of interactionist dualism. He contended that to be phenomenally conscious is actively to evaluate what is in (or might be in) one’s environment, attending to what one decides is important, and ignoring much else. To be conscious is to care about one’s own actual or potential circumstances, in short; and James hypothesized that this caring capacity was selected (in the Darwinian sense) because it regulated the behavior of vertebrates with highly-articulated brains. He did not argue directly for this hypothesis, however. Instead, James recommended the hypothesis as a way to explain some of the surprising physiological results we will have discussed in lecture 1—in particular, experiments purporting to demonstrate purposive behavior in decapitated frogs. I reconstruct and evaluate James’s evolutionary hypothesis, showing how it would explain those surprising experiments.Lecture 3: The Death of Consciousness?Like heartburn, a pronounced discomfort with the very idea of consciousness followed the early days of experimental psychology. Received wisdom has it that psychologists (and allied philosophers) came to mistrust consciousness for largely behaviorist reasons. But by the time John Watson had published his behaviorist manifesto in 1913, a wider revolt against consciousness was already underway. I begin by canvassing some of the lesser-known, pre-behaviorist angst about consciousness. Then I delve into James’s case against consciousness, which was particularly influential. I argue that his rejection of consciousness grew out of his critique of perceptual elementarism in psychology. Elementarism is the view that most mental states are complex, and that psychology’s goal is in some sense to analyze these states into their atomic “elements.” Elementarism came in for intense criticism in James’s Principles of Psychology, and I argue that his later rejection of consciousness is an extension of the earlier critique. Just as we cannot (according to James) isolate any atomic, sensory elements in our occurrent mental states, so we cannot distinguish any elemental consciousness from any separate contents.Lecture 4: The Road not TakenIn my final lecture, I argue that James’s early, evolutionary account of consciousness is compatible with his later rejection of the container/content view. The upshot is that James offered a sophisticated treatment of consciousness over the span of a lifetime, a treatment that represents a road not taken. Behaviorists who were impressed by the negative part of his argument unwittingly discarded a panoply of interesting, positive results that are worth excavating and taking seriously again, today.

Thank you Dr. Oliver for this information. I was reading about Peirce in "The Great Philosophers" by Stangroom and Garvey and saw this quote from Max H. Fisch. "Who is the most original and the most versatile intellect that the Americas have so far produced? The answer 'Charles S. Peirce' is uncontested ... [He was] mathematician, astronomer, chemist, geodesist, surveyor, cartographer, metrologist, spectroscopist, engineer, inventor; psychologist, philologist, lexicographer, historian of science, mathematical economist, lifelong student of medicine; book reviewer, dramatist, actor, short story writer; phenomenologist, semiotician, logician, rhetorician and metaphysician."

ReplyDeleteYet sadly, with all of his knowledge, skills, and accomplishments in so many disciplines, he was forced out of academia, because of "his errant behavior, etc." (although with all of the information circulating in his brain, I'm inclined to believe he would be entitled to a little errant behavior), his job with the U.S. Coastal Survey was ended, and he lived destitute from 1891 to his death in 1914. He survived primarily with the help of some of his friends, one of whom was William James.

Interestingly as of 2012 when this book was published, "some eighthy thousand pages of his work [are] still to be published. With all of the fine sources you included in your post, I can imagine that there will be more to add to that list as more of his writings are published.

Great quote! Peirce's philosophy was complex and far-flung, but the nub of it is that he was a proponent of inquiry as the form of human activity that offers our greatest promise of progress and flourishing. "Don't block the road of inquiry!" was his slogan. His controversial definition of truth was the view that's destined to be agreed upon "at the end of inquiry"... but there's a catch: inquiry will never end, so long as our species continues. Truth, then, must always be held lightly. We must always acknowledge our fallibility, and embrace our errors as much as our successes.

DeleteMy colleague Dr. Magada-Ward is one of Peirce's greatest fans. She always used to write a long Peirce quote on the board in our old JUB classroom on the first day of each semester... and I, more Jamesian than Peircean, always used to go in to meet my first class, and invariably told them I (good-naturedly) disagreed with my colleague and with Peirce. I have an old post with a picture of the quote somewhere, I'll find and post it.

P.S. For those of you still hazy on our "scorecard game," Don's comment earns him a base.

Delete